Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

The standards may be narrative or speciic (numeric) to a certain chemical. An example of a

narrative criterion could be

The waters of the State may not be polluted by … substances … that are unsightly, … odorous, … cre-

ate a nuisance, or interfere directly or indirectly with water uses,

while an example of a numeric criterion could be

the water quality standard for dissolved oxygen may be 5.0 milligrams per liter oxygen for some desig-

nated uses and 6.0 for others.

The standards, particularly the numeric standards, were and are used to determine allowable, or

permitted, loads to waterbodies (the wasteload allocation process) or to determine if a waterbody is

meeting water quality objectives. If waterbodies are not meeting standards, then states must report

this to Congress (in the National Water Quality Inventory Report to Congress or the 305(b) report).

There is also a provision in the CWA for the case where, following the implementation of the

best available technology and/or efluent limitations (for point sources), water standards were not

achieved. Under those conditions, Section 303(d) required that states report impaired waterbodies

to Congress and establish the total maximum daily loads (TMDLs) that were required to meet the

water quality standards. That TMDL included the cumulative impacts of all point sources and non-

point sources, and allowed for a margin of safety. Section 303(d) was largely unenforced until the

early 1990s when lawsuits forced environmental agencies to implement its provisions. Today, as a

result of including nonpoint sources, water quality control and management have shifted from point

source control to watershed management.

5.2 LIGHT

Light is not something for which there is usually a water quality standard, but light (heat energy)

does directly affect temperature and it is, of course, necessary for photosynthesis. To describe the

impact of light on rivers and streams, it is irst necessary to describe the characteristics and fate of

light in the environment.

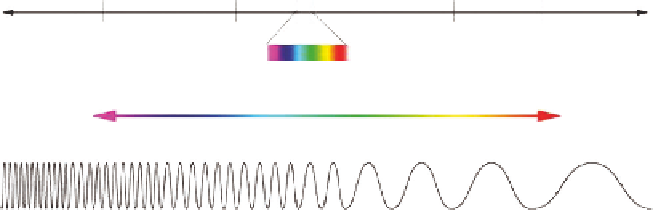

First of all, light is not “a” thing. For example, is light a “wave,” having a wavelength and a

frequency? Or, is light a particle (or a stream of particles, photons, or quanta)? The idea of light as

a wave is suficient for our purposes, and the range of radiation over all wavelengths is called the

electromagnetic spectrum (Figure 5.3). For water quality impacts, we are typically concerned with

only a small portion of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Our primary source of light is from the sun, and the incoming light available near the earth is rel-

atively constant (solar constant = 440 BTU ft.

−2

h

−1

= 1390 W m

−2

). The amount of light reaching

Ultraviolet

Radio

Gamma ray

Infrared

X-ray

Microwave

Visible

Shorter wavelength

Higher frequency

Higher energy

Longer wavelength

Lower frequency

Lower energy

FIGURE 5.3

Electromagnetic spectrum. (From NASA, electromagnetic spectrum, Available at http://

imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l1/emspectrum.html.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search