Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

In any given location, the varves can range from 1/16 in. to several inches in thickness,

or can be so thin as to be discernible only when the specimen is air-dried and broken open.

In Connecticut, the varves range generally from 1/4 to 2

1

2

in. (6-64 mm), whereas in New

Jersey in Glacial Lake Hackensack, they are much thinner, especially in deeper zones where

they range from 1/8 to 1/2 in. (3-13 mm). The New York materials seem to fall between

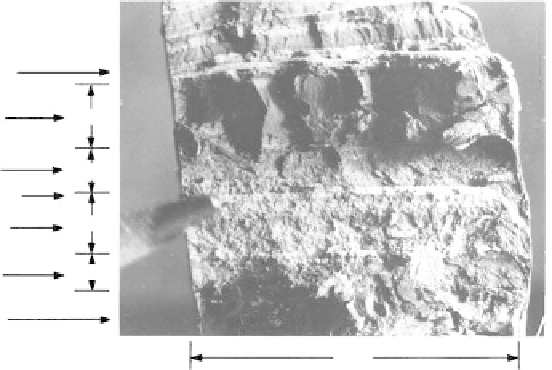

these extremes. Clay and silt varves and sand partings from a tube sample from a depth of

about 22 ft taken from a site in East Rutherford, New Jersey, are shown in

Figure 7.93.

Postdepositional Environments

The engineering characteristics of a given glacial lake deposit will depend directly on the

postdepositional environment, which is associated with its mode of occurrence, and is

subdivided into three general conditions as follows:

Normally consolidated

conditions prevail in swamp and marsh areas where the lake bot-

tom has never been exposed as a surface and subjected to drying, desiccation, and the

resulting prestress. This condition can be found in small valleys in the northeastern United

States, but is relatively uncommon. SPT values are about 0 to 2 blows per foot and the

deposit is weak and compressible.

Overconsolidated

conditions prevail where lake bottoms have been exposed to drying and

prestress from desiccation. At present they are either dry land with a shallow water table

or covered with swamp or marsh deposits. Typically, a crust of stiff soil forms, usually rang-

ing from about 3 to 10 ft in. thickness, which can vary over a given area. The effect of the

prestress, however, can extend to substantial depths below the crust. In many locations, oxi-

dation of the soils in the upper zone changes their color from the characteristic gray to yel-

low or brown. This is the dominant condition existing beneath the cities of the northeast

and northcentral United States. These formations can support light to moderately heavy

structures on shallow foundations, but some small amounts of settlement normally occur.

Heavily overconsolidated

deposits are characteristic of lake bottoms that have been raised,

often many tens of feet, above present river levels, and where the varved clays now form

slopes or are found in depressions above the river valley. This condition is common along

the Hudson River in New York and many rivers of northern New England, such as the

Barton River in Vermont (see

Figure 2.16

and

Figure 2.17).

In the last case, desiccation and

the natural tendency for drainage to occur along silt and sand varves have resulted in a

Sand parting

Clay varve

1.1 cm

Silt varve

0.7 cm

Sand parting

0.9 cm

Silty sands

0.5 cm

Silt varve

Clay varve

5.1 cm

FIGURE 7.93

Shelby tube sample of varved clay (Glacial Lake Hackensack, East Rutherford, New Jersey); depth about 7 m.