Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

ebrated of today's Irish writers is

Roddy Doyle,

whose feel for working-class Dublin res-

onates in his novels of contemporary life (such as

The Commitments

) as well as in histor-

ical slices of life (such as

A Star Called Henry

).

Seamus Heaney,

a poet who has won

the Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, published a new translation in 1999 of the Old English epic

Beowulf

—wedding the old with the new.

TheIrishhavearichoraltraditionthatgoesbacktotheirancientfiresidestorytelling days.

Part of the fun of traveling here is getting an ear for the way locals express themselves.

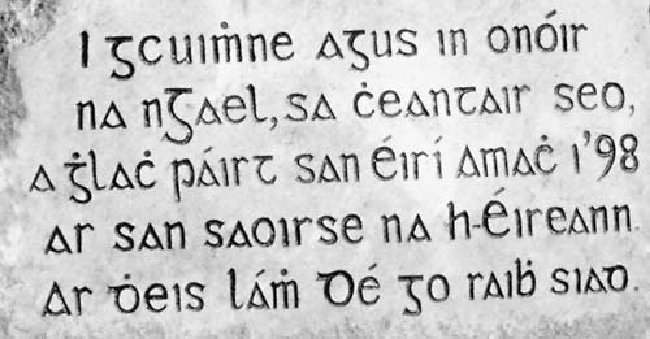

Irish Gaelic is one of four surviving Celtic languages, along with Scottish Gaelic,

Welsh, and Breton (spoken in parts of French Brittany). A couple of centuries ago, there

were seven surviving Celtic languages. But Cornish (spoken in Cornwall) is on life sup-

port, and two others—Manx (from the Isle of Man) and Gallaic (spoken in Northern

Spain)—have died out. Some proud Irish choose to call their native tongue “Irish” instead

of “Gaelic” to ensure that there is no confusion with what is spoken in parts of Scotland.

Only 165 years ago, the majority of the Irish population spoke Irish Gaelic. But most of

the speakers were of the poor laborer class that either died or emigrated during the famine.

After the famine, Irish Gaelic was seen as a badge of backwardness. Parents and teachers

understood that English was the language that would serve children best when they emig-

rated to better lives in the US, Canada, Australia, or England. Children in schools wore a

tally stick around their necks, and a notch was cut by teachers each time a child was caught

speaking Irish. At the end of the day, the child received a whack for each notch in the stick.