Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

supplies in regions or countries that are affected by com-

bat or subjected to prolonged bombing. Given these

realities, it is inexplicable that wars have received so little

attention as energy phenomena. At the same time, there

is a fairly common perception—greatly reinforced by the

U.S. intervention in Iraq in 2003—that energy is often

the main reason why nations go to war. I address all

these issues.

Weapons are the prime movers of war. They are

designed to inflict damage through a sudden release of

kinetic energy (all handheld weapons, projectiles, explo-

sives) or heat, or a combination both. Nuclear weapons

kill almost instantly by combined blast and thermal radi-

ation, and also cause delayed deaths and sickness due to

exposure to ionizing radiation. All prehistoric, classical,

and early medieval warfare was powered only by human

and animal muscles. The invention of gunpowder—clear

directions for its preparation were published in China in

1040, and the proportions for its mixing eventually set-

tled at 75% saltpeter (KNO

3

), 15% charcoal, and 10%

S—led to a rapid diffusion of initially clumsy front- and

breach-loading rifles and to much more powerful field

and ship guns (Smil 1994). While ordinary combustion

must draw oxygen from the surrounding air, the ignited

KNO

3

provides it internally, and gunpowder undergoes

a rapid expansion to about 3,000 times its volume in

gas. The first true guns were cast in China before the

end of the thirteenth century, and Europe was just a few

decades behind.

Gunpowder raised the destructiveness of weapons and

radically changed the conduct of both land and maritime

battles. When confined and directed in rifle barrels, gun-

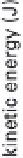

powder imparts to bullets kinetic energy 1 OM higher

than that of a heavy arrow shot from a crossbow gun (1

kJ vs. 100 J); the kinetic energy of iron balls fired from

12.7 Kinetic energy of projectiles, from stone-tipped arrows

to heavy gun shells. Plotted from data in Smil (2004c).

cannons was 3 OM higher. Increasingly accurate gunfire

eliminated the defensive value of moats and walls, and

the impact of guns was even greater in maritime engage-

ments (fig. 12.7). Gunned ships equipped with two other

Chinese innovations, compass and rudder, as well as with

better sails, projected empire-building European power

(Cipolla 1966; McNeill 1989). The dominance of these

ships ended only with the introduction of naval steam

engines during the nineteenth century.

The next weapons era began with the formulation of

high explosives prepared by the nitration of such organic

compounds as cellulose, glycerine, phenol, and toluene.

Ascanio Sobrero prepared nitroglycerin in 1846, but its

practical use began only after Alfred Nobel mixed it with

an inert porous substance (diatomaceous earth) to create