Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

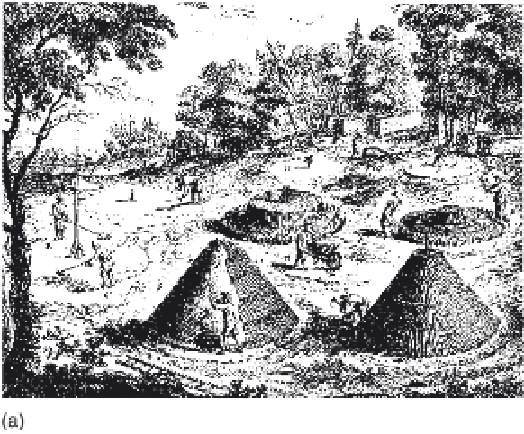

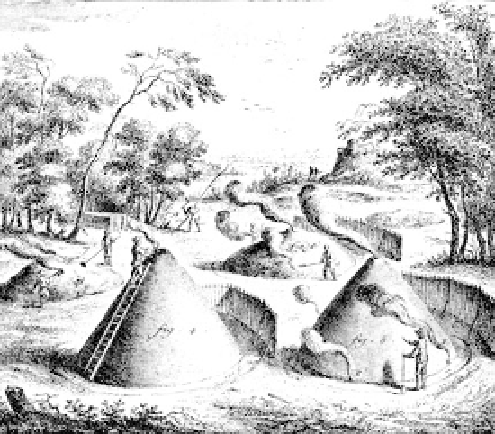

7.8 (a) Building a charcoal pile. (b) Charcoal production in

mid-eighteenth-century France. From Diderot and D'Alembert

(1751-1772).

tional charcoal making was about 60%. In volumetric

terms, primitive earth kilns needed as much as 24 m

3

of

wood per tonne of charcoal, and even for good practices

the average was between 9-10 m

3

.

Considering the generally low levels of final energy

demand (for cooking, rudimentary space heating, and

artisanal manufacturing), consumption of phytomass

fuels in traditional societies was relatively high owing

to often dismally low conversion efficiencies. Transition

from uncontrolled and inherently inefficient open-air

fires to enclosed, regulated, and efficient burners was

very slow. Moving open fire inside made little difference.

Fireplaces that dominated European cooking and heating

for centuries performed quite poorly; as they drew the

needed combustion air from the room, they warmed

the immediate vicinity of the hearth with radiated heat,

but their operation amounted to an overall loss of inte-

rior heat.

There were some ancient ingenious ways of using phy-

tomass efficiently, none more so than three space heating

systems that provided an uncommon degree of comfort.

The first two used combustion gases to heat raised room

floors before leaving through a chimney. The Roman

hypocaust—of Greek origin, with the oldest remains from

the third and second centuries

B

.

C

.

E

., found both in

Greece and in Magna Graecia (Ginouv`s 1962)—was

first used by the Romans in the caldaria of their public

baths, then spread to stone houses in colder provinces of

the empire. The Korean ondol (warm stone) led the hot

combustion gases from the kitchen (or from additional