Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

and we have no idea what fraction of killed animals was

brought to camp sites or how many people it served.

Moreover, extreme spatial variability of the fragmentary

evidence permits no quantitative generalizations.

By the time anthropology was ready to study directly

the energetics of foraging societies (only well after WW

II), most such societies were either extinct or affected by

contact with neighboring pastoralists or farmers. Some

of the best records of relatively unchanged foraging sub-

sistence are available for the !Kung, 0Kade, and G/wi

groups of the Basarwa (Bushmen, the San), gatherers-

hunters of the late 1950s and early 1960s, just before

the rapid disappearance of this traditional way of life

(Lee 1979; Tanaka 1980; Silberbauer 1981), but they

pertain to a marginal environment and tell nothing about

the situation in more equable climates and fertile areas

where gathering and hunting were abandoned millennia

ago in favor of settled cultivation.

Systematic appraisals make clear that forager energetics

is a matter of peculiarities and exceptions rather than

of close similarities and general rules (Lee and De Vore

1968; Service 1979; Winterhalder and Smith l981; Kelly

1983; Price and Brown 1985; Kelly 1995; Gowdy 1998;

Lee and Daly 1999; Stanford and Bunn 2001; Panter-

Brick, Layton, and Rowley-Conwy 2001; Barnard 2004;

Frison 2004). Large differences in habitats and diets

translated into population densities differing by up to 2

OM. Minimum population densities of groups that

depended on mixtures of gathering and hunting activities

were on the order of 1/100 km

2

(tropical Aeta of the

Philippines, the Semang of Malaya, the boreal Micmac

of eastern Canada). The rates were 1 OM higher in sea-

sonally dry tropical environments (Kalahari Basarwa at

7-10/100 km

2

). Groups heavily dependent on fishing

had densities up to 1 OM higher (Pacific Northwest's

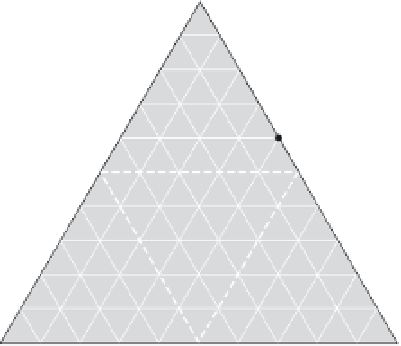

5.9 Approximate contributions of gathering, hunting, and

fishing to the diets of some foraging societies that survived into

the twentieth century. Plotted from data in Murdock (1967).

Nootka and Kwakiutl at about 60/100 km

2

, Makah at

nearly 90/100 km

2

).

Regardless of the prevailing source of food energy (fig.

5.9), large seasonal variations of staple food abundance,

as well as its annual fluctuations, resulted in highly irreg-

ular utilization patterns. Kelly (1983) suggested a cover-

age index (total exploited area/total residential mobility

distance) to indicate the intensity of land utilization. Pre-

dictably, it would be highest for gathering societies and

up to 1 OM lower for hunters. Primary and secondary

productivity and the shares of accessible edible biomass

are the key ecosystemic variables needed to evaluate for-

ager energetics. Forest phytomass is mostly in indigest-

ible lignin and cellulose of tree trunks; fruits and seeds

are a very small portion of the total, are commonly inac-

cessible in high canopies and are often well protected by

hard coats, requiring fairly energy-intensive processing

before consumption.