Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

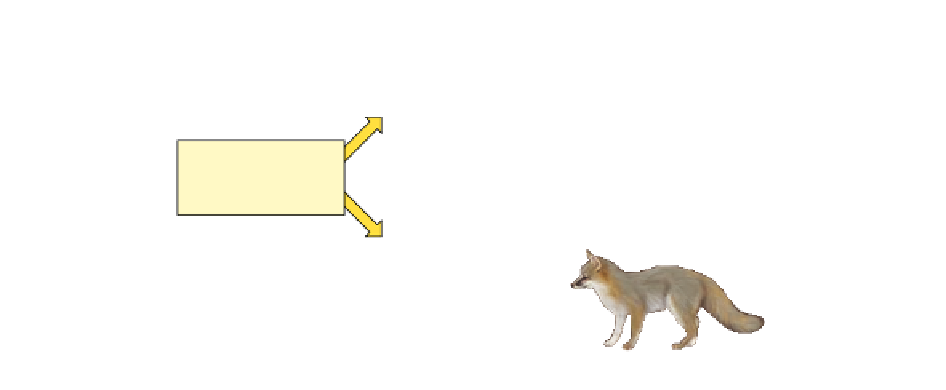

Adapted to cold

through heavier fur,

short ears, short legs,

short nose. White fur

matches snow for

camouflage.

Arctic Fox

Northern

population

Spreads northward

and southward

and separates

Different environmental

conditions lead to different

selective pressures and evolution

into two different species.

Early fox

population

Gray Fox

Southern

population

Adapted to heat

through lightweight

fur and long ears,

legs, and nose, which

give off more heat.

Figure 4-7

Geographic isolation

can lead to reproductive isolation, divergence, and speciation.

In

reproductive isolation,

mutation and natural

selection operate independently in the gene pools of

geographically isolated populations. If this process

continues long enough, members of the geographically

and reproductively isolated populations of sexually re-

producing species may become so different in genetic

makeup that they can never produce live, fertile off-

spring. Then one species has become two, and specia-

tion has occurred.

For some rapidly reproducing organisms, this type

of speciation may occur within hundreds of years. For

most species, it takes from tens of thousands to mil-

lions of years.

Given this time scale, it is difficult to observe and

document the appearance of a new species. Thus many

controversial hypotheses attempt to explain the details

of speciation.

planet, and releases of large amounts of methane

trapped beneath the ocean floor. Some of these events

created dust clouds that shut down or sharply reduced

photosynthesis long enough to eliminate huge num-

bers of producers and, soon thereafter, the consumers

that fed on them.

In some places, populations of existing species

have been reduced or eliminated by newly arrived

migrant species or species that are accidentally or de-

liberately introduced into new areas. More recently,

humans have taken over or degraded many of the

earth's resources and habitats. Today's biodiversity

represents the species that have survived and thrived

despite environmental upheavals.

Background Extinction, Mass Extinction,

and Mass Depletion

All species eventually become extinct, but drastic

changes in environmental conditions can eliminate

large groups of species.

Extinction is the ultimate fate of all species, just as

death awaits all individual organisms. Biologists esti-

mate that 99.9% of all the species that ever existed are

now extinct. The human species will not escape this ul-

timate fate.

As local environmental conditions change, a cer-

tain number of species disappear at a low rate, called

background extinction.

Based on the fossil record and

analysis of ice cores, biologists estimate that the aver-

age annual background extinction rate is one to five

species for each million species on the earth.

In contrast,

mass extinction

is a significant rise in

extinction rates above the background level. In such a

catastrophic, widespread (often global) event, large

groups of existing species (perhaps 25-70%) are wiped

out. Fossil and geological evidence indicates that the

earth's species have experienced five mass extinctions

Extinction: Lights Out

Aspecies becomes extinct when its populations

cannot adapt to changing environmental

conditions.

Another process affecting the number and types of

species on the earth is

extinction,

in which an entire

species ceases to exist. When environmental condi-

tions change drastically enough, a species must evolve

(become better adapted), move to a more favorable

area if possible, or become extinct.

For most of the earth's geological history, species

have faced incredible challenges to their existence.

Continents have broken apart and moved over mil-

lions of years (Figure 4-8, p. 72). The earth's land area

has repeatedly shrunk when continents have been

flooded, has expanded when the world's oceans have

shrunk, and has sometimes been covered with ice.

The earth's life has also had to cope with volcanic

eruptions, meteorites and asteroids crashing onto the