Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

Cockroaches: Nature's Ultimate Survivors

Cockroaches (Fig-

ure 4A), the bugs

many people love

to hate, have been

around for 350

million years. One

of evolution's

great success stories, they have

thrived because they are

generalists.

The earth's 3,500 cockroach

species can eat almost anything, in-

cluding algae, dead insects, finger-

nail clippings, salts in tennis shoes,

electrical cords, glue, paper, and

soap. They can also live and breed

almost anywhere except in polar

regions.

Some cockroach species can go

for months without food, survive

for a month on a drop of water

from a dishrag, and withstand

massive doses of radiation. One

species can survive being frozen for

48 hours.

Cockroaches usually can evade

their predators (and a human foot

in hot pursuit) because most

species have antennae that can

detect minute movements of air,

vibration sensors in their knee

joints, and rapid response times

(faster than you can blink). Some

even have wings.

productive rate helps them quickly

develop genetic resistance to almost

any poison we throw at them.

Most cockroaches sample food

before it enters their mouths, so they

learn to shun foul-tasting poisons.

They also clean up after themselves

by eating their own dead and, if

food is scarce enough, their living.

Only about 25 species of cock-

roach live in homes. Unfortunately,

such species can carry viruses and

bacteria that cause diseases such as

hepatitis, polio, typhoid fever,

plague, and salmonella. They can

also cause people to have allergic

reactions ranging from watery

eyes to severe wheezing. About

60% of Americans suffering from

asthma are allergic to live or dead

cockroaches.

SCIENCE

SPOTLIGHT

Figure 4A

As generalists, cockroaches

are among the earth's most adaptable

and prolific species.

They also have high reproduc-

tive rates. In only a year, a single

Asian cockroach (especially preva-

lent in Florida) and its offspring

can add about 10 million new cock-

roaches to the world. Their high re-

Critical Thinking

If you could, would you extermi-

nate all cockroach species? What

might be some ecological conse-

quences of this action?

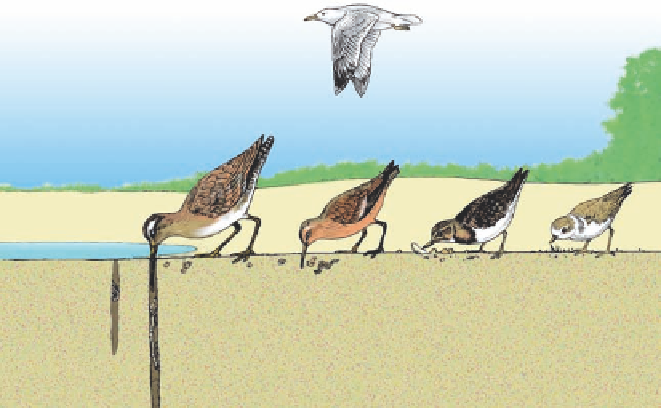

different types of beaks specialized to feed on food

sources such as specific types of insects, nectar from

particular types of flowers, and certain types of seeds

and fruit (Figure 4-6, p. 70).

Limits on Adaptation

A population's ability to adapt to new environmental

conditions is limited by its gene pool and the speed

with which it can reproduce.

Will adaptations to new environmental conditions in

the not too distant future allow our skin to become

more resistant to the harmful effects of ultraviolet radi-

ation, our lungs to cope with air pollutants, and our

liver to better detoxify pollutants? The answer is

no

be-

cause of two limits to adaptations in nature.

Herring gull is a

tireless scavenger

Dowitcher probes deeply

into mud in search of

snails, marine worms,

and small crustaceans

Ruddy turnstone searches

under shells and pebbles

for small invertebrates

Piping plover feeds

on insects and tiny

crustaceans on

sandy beaches

Knot (a sandpiper)

picks up worms and

small crustaceans left

by receding tide

Figure 4-5

Natural capital:

specialized feeding niches of

various bird species in a coastal wetland. Such resource

partitioning reduces competition and allows sharing of limited

resources.

(Birds shown here are not drawn to scale)