Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

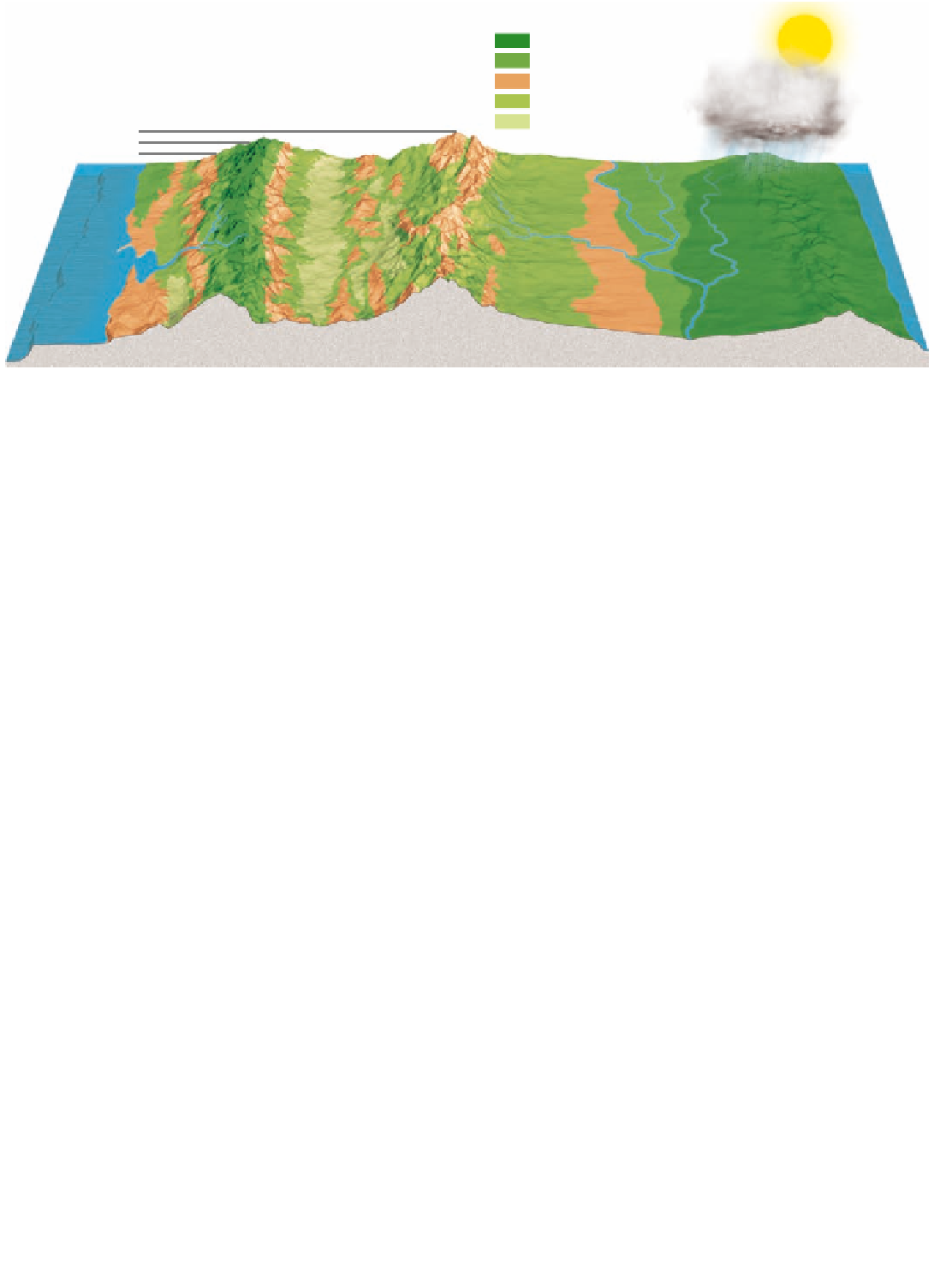

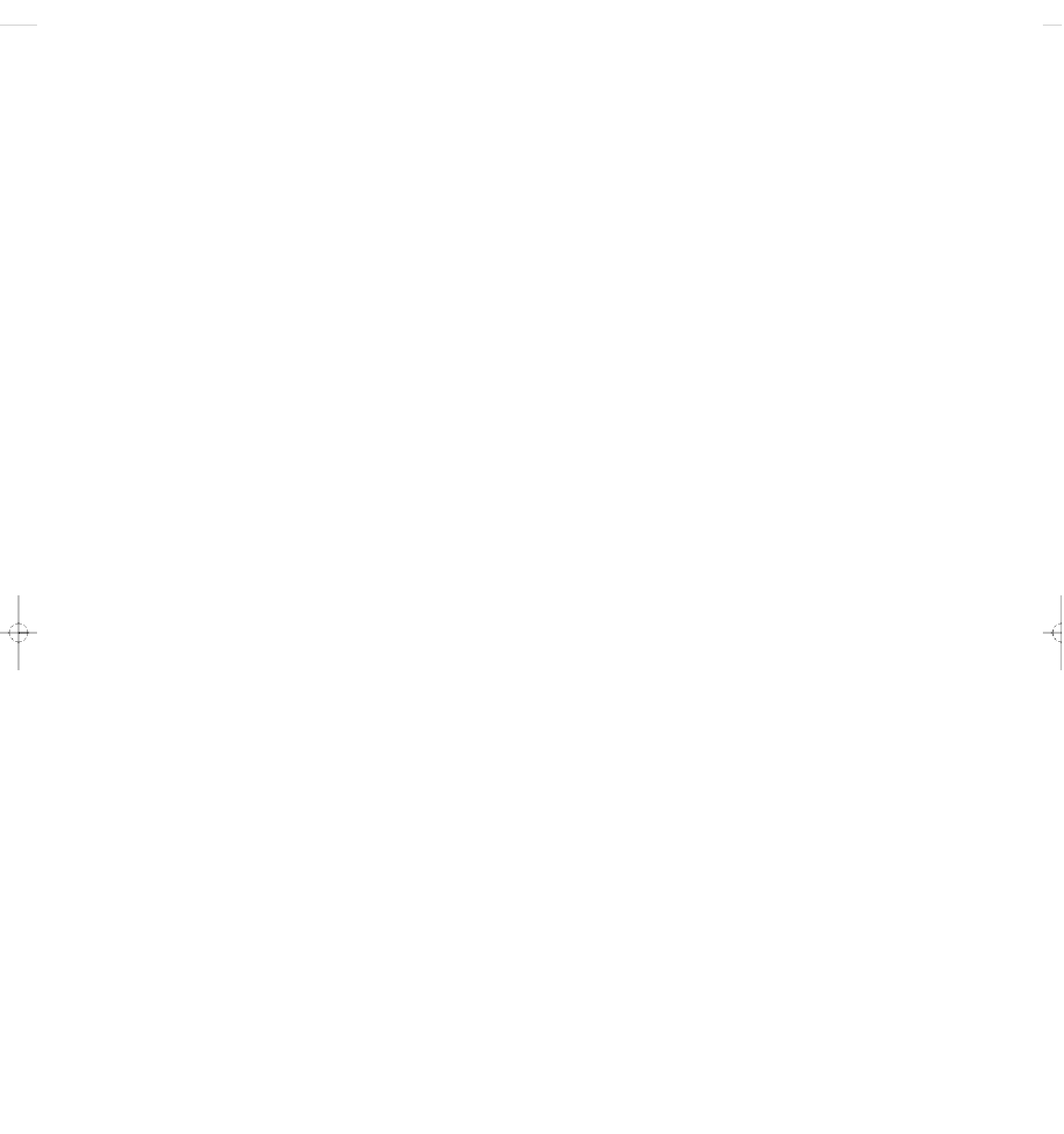

Average annual precipitation

100-125 cm (40-50 in.)

75-100 cm (30-40 in.)

50-75 cm (20-30 in.)

25-50 cm (10-20 in.)

below 25 cm (0-10 in.)

4,600 m (15,000 ft.)

3,000 m (10,000 ft.)

1,500 m (5,000 ft.)

Coastal mountain

ranges

Sierra Nevada

Mountains

Great American

Desert

Rocky

Mountains

Great

Plains

Mississippi

River Valley

Appalachian

Mountains

Coastal chaparral

and scrub

Coniferous forest

Desert

Coniferous forest

Prairie grassland

Deciduous forest

Figure 3-8

Natural capital:

major biomes found along the 39th parallel across the United States. The differ-

ences reflect changes in climate, mainly differences in average annual precipitation and temperature.

systems. Examples include

freshwater life zones

(such as

lakes and streams) and

ocean

or

marine life zones

(such

as coral reefs, coastal estuaries, and the deep ocean).

cool or cold one. Some do best under wet conditions;

others succeed under dry conditions.

Each population in an ecosystem has a

range of

tolerance

to variations in its physical and chemical en-

vironment, as shown in Figure 3-11 (p. 43). Individuals

within a population may also have slightly different

tolerance ranges for temperature or other factors be-

cause of small differences in genetic makeup, health,

and age. For example, a trout population may do best

within a narrow band of temperatures (

optimum level or

range

), but a few individuals can survive above and

below that band. Of course, if the water becomes too

hot or too cold, none of the trout can survive.

These observations are summarized in the

law of

tolerance:

The existence, abundance, and distribution of a

species in an ecosystem are determined by whether the levels

of one or more physical or chemical factors fall within the

range tolerated by that species.

A species may have a

wide range of tolerance to some factors and a narrow

range of tolerance to others. Most organisms are least

tolerant during juvenile or reproductive stages of their

life cycles. Highly tolerant species can live in a variety

of habitats with widely different conditions.

Nonliving and Living Components

of Ecosystems

Ecosystems consist of nonliving (abiotic) and living

(biotic) components.

Two types of components make up the biosphere and

its ecosystems:

abiotic

or nonliving components such

as water, air, nutrients, and solar energy and

biotic

or

living biological components such as plants, animals,

and microbes.

Figures 3-9 and 3-10 (p. 42) are greatly simplified

diagrams of some of the biotic and abiotic components

in a freshwater aquatic ecosystem and a terrestrial

ecosystem. Look carefully at these components and

how they are connected to one another through the

consumption habits of organisms.

Different species thrive under different physical

conditions. Some need bright sunlight; others thrive in

shade. Some need a hot environment; others prefer a