Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

added to the GDP. Examples include unpaid volunteer

work, health care for family members, child care, and

housework. Then the estimated harmful environmen-

tal costs (such as pollution and resource depletion and

degradation) and social costs (such as crime) are sub-

tracted from the GDP.

All economic goods and services have

internal

or

direct

costs

associated with producing them. For example, if

you buy a car, the direct price you pay includes the costs

of raw materials, labor, and shipping, as well as a

markup to allow the car company and its dealers to earn

some profits. Once you buy the car, you must pay addi-

tional direct costs for gasoline, maintenance, and repair.

Making, distributing, and using economic goods

or services also lead to

indirect

or

external costs

that are

not included in their market prices and that affect peo-

ple other than the buyer and seller. For example, ex-

tracting and processing raw materials to make a car

use nonrenewable energy and mineral resources, pro-

duce solid and hazardous wastes, disturb land, and

pollute the air and water. These external costs can have

short- and long-term harmful effects on other people

and on the earth's life-support systems.

Because these costs are not included in the market

price, most people do not connect them with car own-

ership. Even so, the car buyer and other people in a so-

ciety pay these hidden costs sooner or later, in the form

of poorer health, higher costs of health care and insur-

ance, higher taxes for pollution control, traffic conges-

tion, and land used for highways and parking.

Genuine

benefits not

harmful

progress GDP

included in

environmental

indicator

market transactions

and social costs

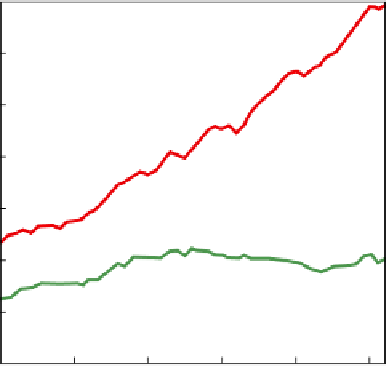

Figure 18-6 compares the per capita GDP and GPI

for the United States between 1950 and 2002. While the

per capita GDP rose sharply over this period, the per

capita GPI stayed nearly flat and even declined slightly

between 1975 and 2002.

The GPI and other environmental indicators un-

der development are far from perfect and include

many crude estimates. Nevertheless, without such in-

dicators, we would not know much about what is hap-

pening to people, the environment, and the planet's

natural capital. With them, we have a way to deter-

mine which policies work. In essence, according to

ecological and environmental economists, if we ignore

these indicators, we attempt to guide national and

global economies through treacherous economic and

environmental waters at ever-increasing speeds using

faulty radar.

Full-Cost Pricing

Including external costs in market prices informs

consumers about the impacts that their purchases

have on the earth's life-support systems and human

health.

For most economists, an

environmentally honest market

system

provides a way to deal with the harmful costs of

goods and services. In this system, the harmful indi-

rect or external costs of goods and services are in-

cluded in the market price of any good or service, so

that its price comes as close as possible to its

full

cost

—its internal costs plus its external costs. Such a

system would allow consumers to make more in-

formed choices because they would be aware of most

or all of the costs involved when they buy something.

Full-cost pricing encourages producers to invent

more resource-efficient and less-polluting methods of

production, thereby cutting their production costs.

Jobs would be lost in environmentally harmful busi-

nesses as consumers more often choose green prod-

ucts, whereas jobs would be created in environmen-

tally beneficial businesses. If a shift to full-cost pricing

took place over several decades, most environmentally

harmful businesses would have time to transform

themselves into environmentally beneficial businesses.

Likewise, consumers would have time to adjust their

buying habits and learn to purchase more environmen-

tally friendly products and services.

Full-cost pricing seems to make a lot of sense. So

why is it not used more widely? Two major reasons ex-

plain why.

Internal and External Costs

The direct price you pay for something does not

include indirect environmental, health, and other

harmful costs associated with its production

and use.

35,000

30,000

25,000

20,000

15,000

10,000

5,000

Per capita genuine progress indicator (GPI)

0

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

Year

Figure 18-6

Comparison of the per capita gross domestic

product (GDP) and per capita genuine progress indicator

(GPI) in the United States between 1950 and 2002. (Data from

Redefining Progress, 2004)