Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

intensified coastal storms and hurricanes, and tropical

waterborne and insect-transmitted infectious diseases

spreading rapidly beyond their current ranges.

These possibilities were supported by a 2003 analy-

sis carried out by Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall for

the U.S. Department of Defense. They concluded that

global warming “must be viewed as a serious threat to

global stability and should be elevated beyond a scien-

tific debate to a U.S. national security concern.” In 2004,

the United Kingdom's chief science adviser, David A.

King, wrote, “In my view, climate change is the most se-

vere problem we are facing today—more serious even

than the threat of terrorism.”

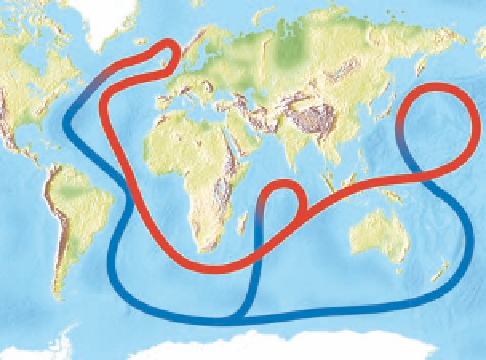

Warm, shallow

current

Cold, salty,

deep current

Figure 16-9

Natural capital:

A connected loop of shallow

and deep ocean currents stores CO

2

in the deep sea and

transmits warm and cool water to various parts of the earth. It

occurs when ocean water in the North Atlantic near Iceland is

dense enough (because of its salt content and cold tempera-

ture) to sink to the ocean bottom, flow southward, and then

move eastward to well up in the warmer Pacific. A shallower

return current aided by winds then brings warmer and less

salty—and thus less dense—water to the Atlantic. This water

can cool and sink to begin the cycle again. A warmer planet

would be a rainier one, which, coupled with melting glaciers,

would increase the amount of fresh water flowing into the North

Atlantic. This could slow or even jam the loop by diluting the

saltwater and making it more buoyant (less dense) and less

prone to sinking.

16-3 FACTORS AFFECTING

THE EARTH'S TEMPERATURE

Scientists have identified a number of natural and hu-

man-influenced factors that might

amplify

or

dampen

projected changes in the average temperature of the

troposphere. The fairly wide range of projected future

temperature changes shown in Figure 16-8 results from

including what is known about these factors in climate

models. Let us examine some possible wild cards that

could make matters worse or better during this century.

Science: Can the Oceans Store More CO

2

and Heat?

There is uncertainty about how much CO

2

and heat

the oceans can remove from the troposphere and how

long they might remain in the oceans.

According to a 2004 study by Christopher L. Sabine and

other researchers, the oceans help moderate the earth's

average surface temperature by removing about 48% of

the excess CO

2

we pumped into the atmosphere as part

of the global carbon cycle between 1800 and 1994. They

also absorb heat from the atmosphere and slowly trans-

fer some of it to the deep ocean, where it is removed

from the climate system for unknown periods.

Ocean currents on the surface and deep down are

connected and act like a gigantic conveyor belt to store

CO

2

and heat in the deep sea and to transfer hot and

cold water from the tropics to the poles (Figure 16-9).

This loop of water flow is propelled by winds and dif-

ferences in water density, which changes with the tem-

perature and salinity of seawater. In a warmer world,

an influx of fresh water from increased rain in the

North Atlantic and thawing ice in the Arctic region

might slow or disrupt this conveyor belt, causing dras-

tic climate changes in as little as a decade.

Large changes in the speed of this conveyor belt

and its stopping and starting may have contributed to

wild swings in northern hemisphere temperatures

during past ice ages. Scientists are trying to learn more

about how this belt operates to evaluate the likelihood

of it slowing down or stalling during this century, and

the effects this might have on regional and global at-

mospheric temperatures.

The large loop of shallow and deep ocean cur-

rents shown in Figure 16-9 helps keep much of the

northern hemisphere fairly warm by pulling warm

tropical water north, pushing cold water south, and

releasing much of the heat stored in the water into the

troposphere.

If this loop of currents should slow sharply or shut

down, northern Europe and the northeast coast of

North America would experience severe regional cool-

ing. In other words,

global warming can lead to signifi-

cant global cooling in some parts of the world.

Disruption

or significant slowing of the loop would also disrupt

other parts of the world with floods, droughts, severe

storms, and searing heat.

Science: Effects of Cloud Cover

Warmer temperatures create more clouds that could

warm or cool the troposphere, but we do not know

which effect might dominate.

A major unknown in global climate models is how

changes in the global distribution of clouds might alter

the temperature of the troposphere. Warmer tempera-

tures increase evaporation of surface water and create

more clouds. These additional clouds can have a

warm-