Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

of nonrenewable mineral resources. Instead, they claim

that the major problem is the environmental damage

caused by their extraction, processing, and conversion

to products (Figure 12-12).

The environmental impacts from mining an ore

are affected by its percentage of metal content, or

grade.

The more accessible and higher-grade ores are

usually exploited first. As they are depleted, it takes

more money, energy, water, and other materials to ex-

ploit lower-grade ores. This, in turn, increases land

disruption, mining waste, and pollution.

For example, gold miners typically remove an

amount of ore equal to the weight of 50 automobiles to

extract a piece of gold that would fit inside your

clenched fist. Most newlyweds would be surprised to

know that about 5.5 metric tons (6 tons) of mining

waste was created to make their two gold wedding

rings. In Australia and North America, a mining tech-

nology called

cyanide heap leaching

is cheap enough to

allow mining companies to level entire mountains

containing very low-grade gold ore.

Currently, most of the harmful environmental

costs of mining and processing minerals are not in-

cluded in the prices for processed metals and the re-

sulting consumer products. Instead, these costs are

passed on to society and future generations, which

gives mining companies and manufacturers little in-

centive to reduce resource waste and pollution. Envi-

ronmentalists and some economists call for phasing in

full-cost pricing

—including the cost of environmental

harm done in the price of goods made from minerals.

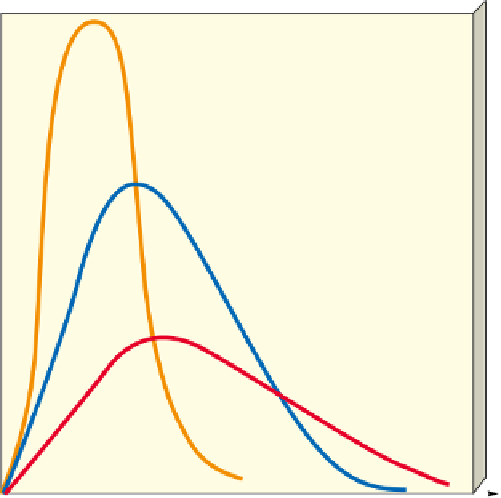

Depletion time

is how long it takes to use up a

certain proportion—usually 80%—of the reserves of a

mineral at a given rate of use. When experts disagree

about depletion times, it is often because they are us-

ing different assumptions about supply and rate of use

(Figure 12-14).

The shortest depletion time assumes no recycling

or reuse and no increase in reserves (curve A, Figure 12-

14). A longer depletion time assumes that recycling will

stretch existing reserves and that better mining tech-

nology, higher prices, and new discoveries will in-

crease reserves (curve B, Figure 12-14). An even longer

depletion time assumes that new discoveries will fur-

ther expand reserves and that recycling, reuse, and re-

duced consumption will extend supplies (curve C, Fig-

ure 12-14). Finding a substitute for a resource leads to a

new set of depletion curves for the new resource.

We can use geological methods to make fairly good

estimates of the reserves of most resources (Figure 12-7,

blue) and less accurate measurements of potential

other supplies of mineral resources (Figure 12-7, red).

Rising prices and improved mining technology can

convert some of the other resources to reserves, but it is

difficult to project how much this conversion will add

to the usable supply.

The demand for mineral resources is increasing at

a rapid rate as more people consume more stuff. For

example, since 1940 Americans alone have used up as

A

Mine, use, throw away;

no new discoveries;

rising prices

x

H

OW

W

OULD

Y

OU

V

OTE

?

Should market prices of goods

made from minerals include their harmful environmental

costs? Cast your vote online at http://biology.brookscole.com

/miller11.

Recycle; increase reserves

by improved mining

technology, higher prices,

and new discoveries

B

12-6 SUPPLIES OF MINERAL

RESOURCES

Recycle, reuse, reduce

consumption; increase

reserves by improved

mining technology,

higher prices, and

new discoveries

Science and Economics: Supplies of

Nonrenewable Mineral Resources

The future supply of a resource depends on how

available and affordable it is and how rapidly that

supply is used.

The future supply of nonrenewable minerals depends

on two factors: the actual or potential supply of the

mineral and the rate at which we use it.

We never completely run out of any mineral. How-

ever, a mineral becomes

economically depleted

when it

costs more to find, extract, transport, and process the

remaining deposit than it is worth. At that point, there

are five choices:

recycle or reuse existing supplies, waste

less, use less, find a substitute,

or

do without.

C

Present

Depletion

time A

Depletion

time B

Depletion

time C

Time

Figure 12-14

Natural capital depletion:

depletion curves

for a

nonrenewable resource (such as aluminum or copper) using three

sets of assumptions. Dashed vertical lines represent times when 80%

depletion occurs.