Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

Before discharge, water from primary, secondary,

or more advanced treatment undergoes

bleaching

to re-

move water coloration and

disinfection

to kill disease-

carrying bacteria and some (but not all) viruses. The

usual method for accomplishing this is

chlorination.

However, chlorine can react with organic materials in

water to form small amounts of chlorinated hydrocar-

bons. Some of these chemicals cause cancers in test an-

imals and may damage the human nervous, immune,

and endocrine systems.

Use of other disinfectants, such as ozone and ul-

traviolet light, is increasing. These options cost more

and their effects do not last as long as chlorination.

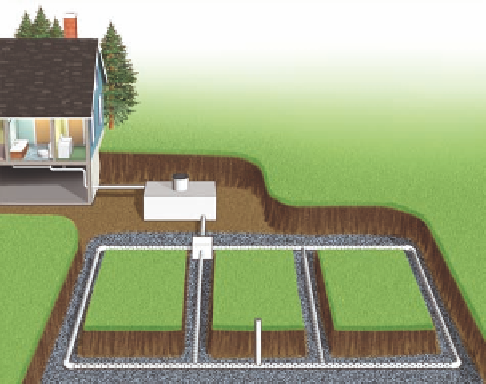

Household

wastewater

Septic tank with

manhole (for cleanout)

Nonperforated pipe

Distribution box (optional)

Gravel or

crushed

stone

Drain

field

Vent pipe

Science: Improving Sewage Treatment

Preventing toxic chemicals from reaching sewage

treatment plants would eliminate such chemicals from

the sludge and water discharged from such plants.

Environmental scientist Peter Montague calls for re-

designing the sewage treatment system. The idea is to

prevent toxic and hazardous chemicals from reaching

sewage treatment plants and thus from getting into

sludge and the water discharged from such plants.

Montague suggests several ways to do this. We

could require industries and businesses to remove

toxic and hazardous wastes before sending water to

municipal sewage treatment plants. We could also en-

courage industries to reduce or eliminate their use and

waste of toxic chemicals.

Another suggestion is to have more households,

apartment buildings, and offices eliminate sewage

outputs by switching to waterless

composting toilet sys-

tems.

Such systems would be cheaper to install and

maintain than current sewage systems because they

do not require vast systems of underground pipes con-

nected to centralized sewage treatment plants. They

also save large amounts of water.

Perforated pipe

Figure 11-32

Solutions:

septic tank system

used for disposal

of domestic sewage and wastewater in rural and suburban ar-

eas. This system separates solids from liquids, digests organic

matter and large solids, and discharges the liquid wastes in a

network of buried pipes with holes located over a large

drainage or absorption field. As these wastes drain from the

pipes and percolate downward, the soil filters out some poten-

tial pollutants, and soil bacteria decompose biodegradable ma-

terials. To be effective, septic tank systems must be properly in-

stalled in soils with adequate drainage, not placed too close to-

gether or too near well sites, and pumped out when the settling

tank becomes full.

In rural and suburban areas with suitable soils, sewage

from each house usually is discharged into a

septic

tank

(Figure 11-32). One-fourth of all homes in the

United States are served by septic tanks.

In U.S. urban areas, most waterborne wastes from

homes, businesses, factories, and storm runoff flow

through a network of sewer pipes to

wastewater

or

sewage treatment plants.

Raw sewage reaching a treat-

ment plant typically undergoes one or two levels of

wastewater treatment. The first level,

primary sewage

treatment,

is a

physical

process that uses screens and a

grit tank to remove large floating objects and solids

such as sand and rock, and a settling tank that allows

suspended solids to settle out as sludge (Figure 11-33).

A second level,

secondary sewage treatment,

is a

bio-

logical

process in which aerobic bacteria remove as

much as 90% of dissolved and biodegradable, oxygen-

demanding organic wastes.

Because of the Clean Water Act, most U.S. cities

have combined primary and secondary sewage treat-

ment plants. According to the EPA, however, at least

two-thirds of these plants have sometimes violated wa-

ter pollution regulations. Also, 500 cities have failed to

meet federal standards for sewage treatment plants,

and 34 East Coast cities simply screen out large floating

objects from their sewage before discharging it into

coastal waters.

Solutions: Treating Sewage by Working

with Nature

Natural and artificial wetlands and other ecological

systems can be used to treat sewage.

John Todd has developed an ecological approach to

treating sewage, which he calls

living machines

(Fig-

ure 11-34). His purification process begins when

sewage flows into a passive solar greenhouse or out-

door sites containing rows of large open tanks popu-

lated by an increasingly complex series of organisms. In

the first set of tanks, algae and microorganisms decom-

pose organic wastes, with sunlight speeding up the

process. Water hyacinths, cattails, bulrushes, and other

aquatic plants growing in the tanks take up the result-

ing nutrients.

After flowing though several of these natural pu-

rification tanks, the water passes through an artificial