Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

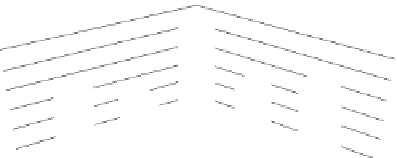

One obvious management response to habitat loss is to protect as much as possible

of what remains, and to include in a network of reserves examples of the variety of

natural habitats that exist. In fact, protected areas of various kinds (national parks,

nature reserves, sites of special scientifi c interest, etc.) grew both in number and

area during the twentieth century. But only about 7.9% of the world's land area is

protected (and 0.5% of sea area - Balmford et al., 2002) and, moreover, there is

the disturbing fact that most large reserves are on land that no one else wanted

(Figure 1.10).

Protection of wilderness is important and, in one sense, 'relatively' easy to achieve.

This is because wilderness is inhospitable to humans and therefore diffi cult to

exploit. (But threats emerge if valuable minerals are discovered in such pristine

settings.) However, distributions of endangered plant and animal species sometimes

overlap with human population centers. To conserve maximum diversity, it follows

that greater focus must be placed in future on areas of higher human value. A global

trend toward reduced government subsidies for agriculture and the lowering of

international trade barriers may have fortunate consequences for the protection of

biodiversity. Thus, in Europe, North America and elsewhere, 'marginal' agricultural

land is becoming increasingly uneconomic to farm. Mass-membership organiza-

tions, such as the Wilderness Foundation and the Royal Society for the Protection

of Birds, have been responding to the opportunity by purchasing some of this land

for 're-wilding'. The restoration of biodiverse grasslands and woodlands will add

somewhat to the total area of the world that is protected for biodiversity.

1.2.5

Invaders -

unwanted biodiversity

Travel has boomed, the world has shrunk and, just like people, plant and animal

species have become globetrotters, sometimes transported to a new region on

purpose but often as accidental tourists. Only about 10% of invaders become estab-

lished and perhaps 10% of these spread and have signifi cant consequences but, when

they do, the effects can be dramatic. Take, for example, the huge loss of native fi sh

biodiversity in Lake Victoria after the introduction of Nile perch. A more 'subtle'

example concerns the arrival in South Africa of the

Var roa

mite, a species that para-

sitizes the larvae of honeybees in hives and wild nests. Commercial operators can

use pesticides to keep the mite in check but 'natural' bee colonies are likely to be

wiped out. This will put plant biodiversity at risk because 50-80% of South Africa's

native fl owers are pollinated by bees (Enserink, 1999).

Fig. 1.10

Most national

parks and nature

reserves in southwest

Australia are situated in

unproductive areas (low

soil fertility) in

inaccessible terrain

(steep topography).

These areas have never

been in demand for

agriculture or urban

development. This

pattern is repeated

around the world.

(After Pressey, 1995;

Bibby, 1998.)

24

20

16

12

8

4

0

Low

Steep

Moderate

Moderate

High

Flat

Search WWH ::

Custom Search