Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

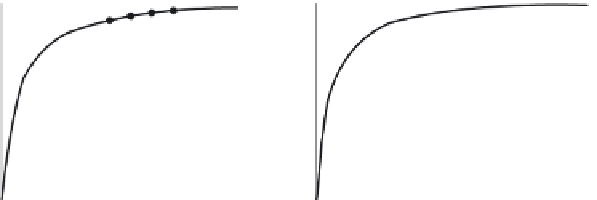

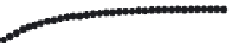

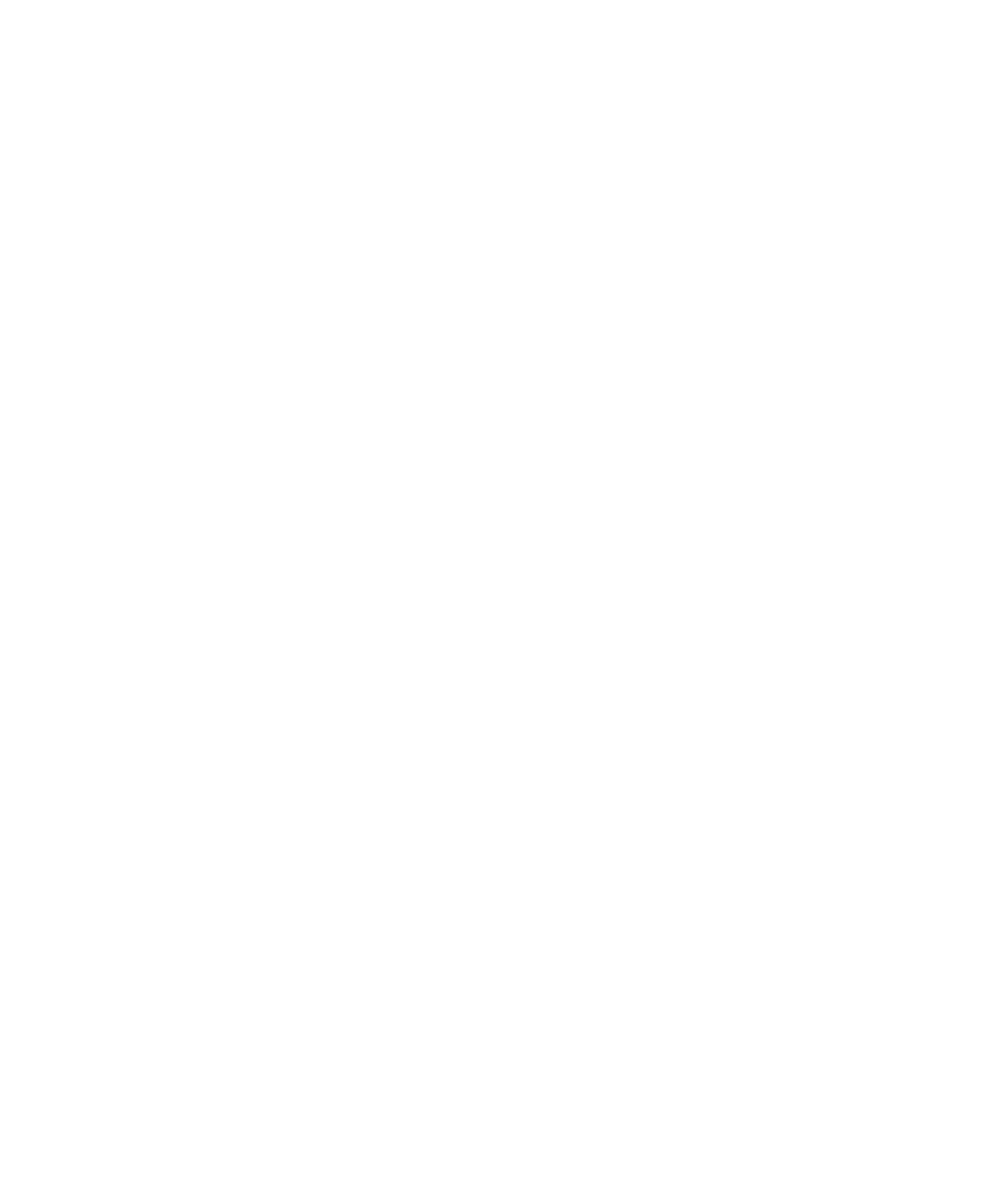

Fig. 9.16

Relative

contributions of species

to ecosystem services

(species shown in order

of the size of their

contribution). (a)

Cumulative watermelon

pollination of 11 native

bee species in Califor-

nia. (b) Cumulative

contribution to carbon

storage of more than 40

tree species in tropical

rainforest at Chiapas in

Mexico. (After

Balvanera et al., 2005.)

(a)

(b)

100

100

80

80

60

60

40

40

20

20

0

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

Species rank

Species rank

live in neighboring patches of intact forest (Section 4.5.4). In the case of organic

watermelon farms close to intact forest, various species of native bee make a con-

tribution to pollination - calculated as the product of bee abundance and pollen

grains transported per individual. When ranked in order of contribution it becomes

clear that just one species is responsible for more than 60% of the pollination eco-

system service (Figure 9.16a). Knowledge of its niche and habitat requirements

would be paramount when countering any threats that may become apparent. Simi-

larly, between them the forest trees of a protected Mexican rainforest store about 94

tonnes of carbon per hectare. But just 13% of the tree species contribute 90% of

carbon storage (being more abundant and/or bigger and/or with denser wood)

(Figure 9.16b). An emerging threat to one or more of these key species (perhaps a

disease) could have a profound effect on the C-storage ecosystem service.

9.8.2

Ecosystem

health of forests -

with all their mites

Many ecosystems around the world have been degraded by human activities. Using

an analogy with the human condition, managers frequently describe ecosystems as

'unhealthy' if their community structure (species richness, species composition,

food web architecture), or their ecosystem functioning (productivity, nutrient

dynamics, decomposition rate), has been fundamentally upset by human pressures.

Aspects of ecosystem health are sometimes refl ected directly in human health. These

include nitrogen content in groundwater and thus drinking water, toxic algal out-

breaks in lake and ocean, and transmission of Lyme disease in oak forest fragments.

But any measure of ecosystem health must also refl ect whether valued ecosystem

services remain intact.

Management strategies c an be usef ully framed in terms of

pressure

(human action),

state

(resulting community structure and ecosystem functioning) and management

response

(Figure 9.17). Just as physicians use indicators in their assessment of human

health (body temperature, blood pressure, etc.), ecosystem managers need ecosys-

tem health indicators when prioritizing ecosystems for action and, just as important,

to enable them to determine whether their interventions have succeeded.

The Ponderosa pine forest (

Pinus ponderosa

) of the western USA illustrates the

relationship between pressure, state and response (Yazvenko & Rapport, 1997). A

variety of human infl uences are at play but the most important

pressure

has been

fi re suppression. Ponderosa pine forest evolved in a situation where periodic fi res

occurred naturally but, with human occupation, attempts to suppress fi re have

caused the

state

of the forest to shift towards lower productivity and higher tree

Search WWH ::

Custom Search