Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

the abalone fi shery sustainable even when all links in the food web (including the

otters) are fully restored.

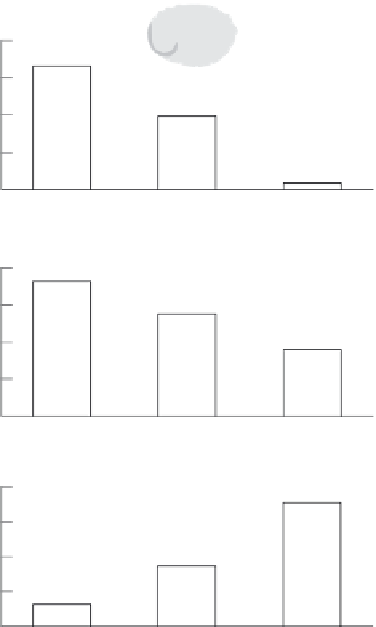

Sea otters and recreational harvest infl uence red abalone populations in similar

ways but the effects of sea otters are much more pronounced. Abalone populations

in protected areas have much higher densities than areas with otters, while har-

vested areas generally have intermediate densities (Figure 9.5a). In addition, there

are differences in the size of abalone (Figure 9.5b) -

63-83% of individual abalones

in protected areas are larger than the legal harvesting limit of 178 mm, compared

with 18-26% in harvested areas and less than 1% in sea otter areas. Clearly the

effects of otters on the size class structure of their abalone prey mean that almost

none are left for human harvest. Finally, in the presence of sea otters the abalones

are mainly restricted to crevices where they are least vulnerable to predation (Figure

9.5c), and most diffi cult for fi shers to extract. Multiple-use protected areas are never

likely to be feasible where a desirable top predator feeds intensively on prey targeted

by a fi shery. Fanshawe's team recommends separate single-purpose categories of

protected area. But this may not work in the long term either. Maintenance of

abalone no-take areas when sea otters are expanding their range will eventually

require culling of otters, something that may not be politically acceptable.

(a)

Fig. 9.5

The infl uence

of human harvest and

otter predation history

on key features of the

abalone population at

sites on the Californian

coast: (a) mean abalone

density; (b) shell

length; (c) percentage

in crevices, where they

are least vulnerable to

predation. (Redrawn

from Fanshawe et al.,

2003.)

20

15

10

5

0

(b)

200

150

100

50

0

(c)

100

0

No harvest and

no otters

Harvest and

no otters

Otters and

no harvest

Search WWH ::

Custom Search