Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

visioning service

(coral cr ushed to create road surface) can result in the loss of a

regulating service

.

Each ecosystem service has a value that can be set against the economic returns

of activities that put them in jeopardy. Thus, in purely economic terms, there are

credible grounds for protecting nature. However, it is not straightforward to recog-

nize ecosystem decline or to know that, by some management action, ecosystem

health has been regained. For this reason, managers need indicators of ecosystem

health that provide a short cut to identifying ecosystems in trouble (Sections

9.8.2-9.8.5).

Box 9.1

Food webs and

pathways of energy and

nutrients

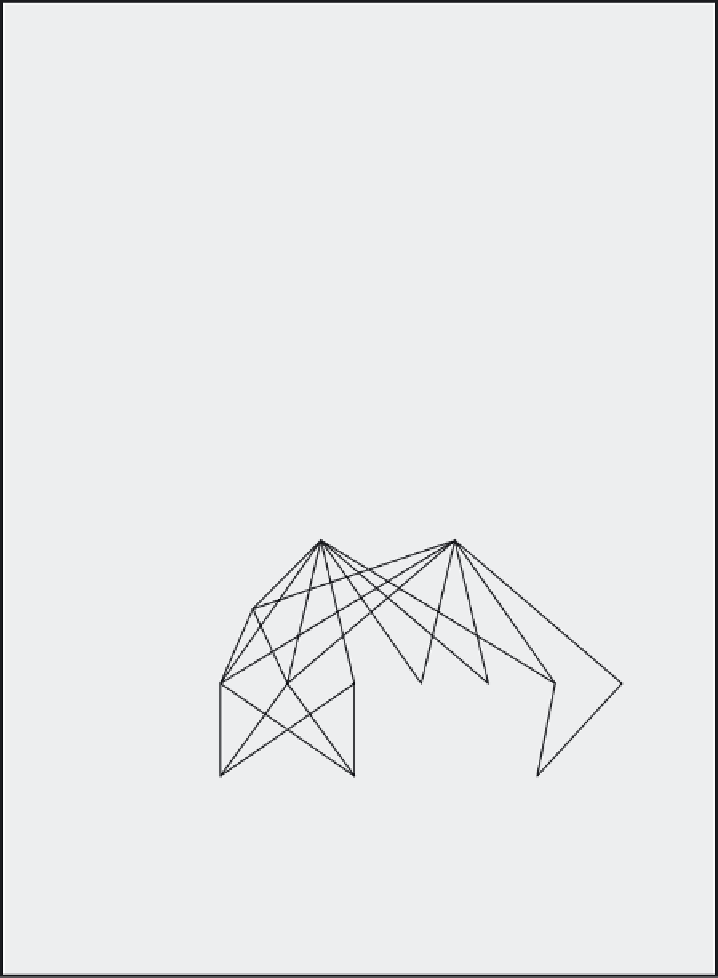

Direct and indirect effects in food webs

A predator feeding on a prey species has its most obvious (and direct) impact on the prey popula-

tion. A similarly straightforward effect in the case of interspecifi c competition is for one competitor

species to negatively impact another that feeds on the same limited resource. However, the infl u-

ence of a species often spreads much further than this, producing a series of indirect effects

throughout the community food web. Thus, for example, the effects of a carnivore on its herbivore

prey may also be felt by any plant population fed upon by the herbivore, by other predators and

parasites of the herbivore, and by other herbivores with which our species competes. The descrip-

tion of food webs is a painstaking affair, involving a detailed taxonomic inventory and analysis of

who feeds on whom. But a huge amount of information is then boiled down into a simple fl ow

diagram such as the one in Figure 9.1. The food web is often a starting point for understanding the

consequences of species loss (e.g. removing predators to assist an endangered species) or species

gain (e.g. reintroducing a desirable species or assessing the risk posed by the invasion of an

undesirable one).

Strong interactors and keystone species

Certain species are more tightly woven into the fabric of the food web than others. A species whose

removal would produce a large change in density (or extinction) of at least one other species may

be described as a

strong interactor

. Some strong interactors, if they were to be removed, would

lead to marked changes spreading throughout the food web

-

these

keystone species

have an

impact that is disproportionately large relative to their abundance (Power et al., 1996). The fi rst

use of the term keystone species was for the starfi sh

Pisaster ochraceus

(Paine, 1966, and see

12

13

11

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

1

2

3

Fig. 9.1

Food web for a rocky shore in Washington State, USA. Species higher in the web

feed on species lower down, as indicated by the lines. 1, fi ne particulate organic detritus in

the water column; 2, free-living microscopic planktonic plants; 3, algae growing on the

rocks; 4, acorn barnacles; 5, the mussel

Mytilus edulis

; 6, the goose barnacle

Pollicipes

sp.; 7,

chitons; 8, limpets; 9, the topshell

Teg ula

sp.; 10, the periwinkle

Littorina

sp.; 11, the snail

Thais

sp.; 12, the starfi sh

Pisaster ochraceus

; 13, the starfi sh

Leptasterias

sp. (After Briand,

1983.)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search