Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

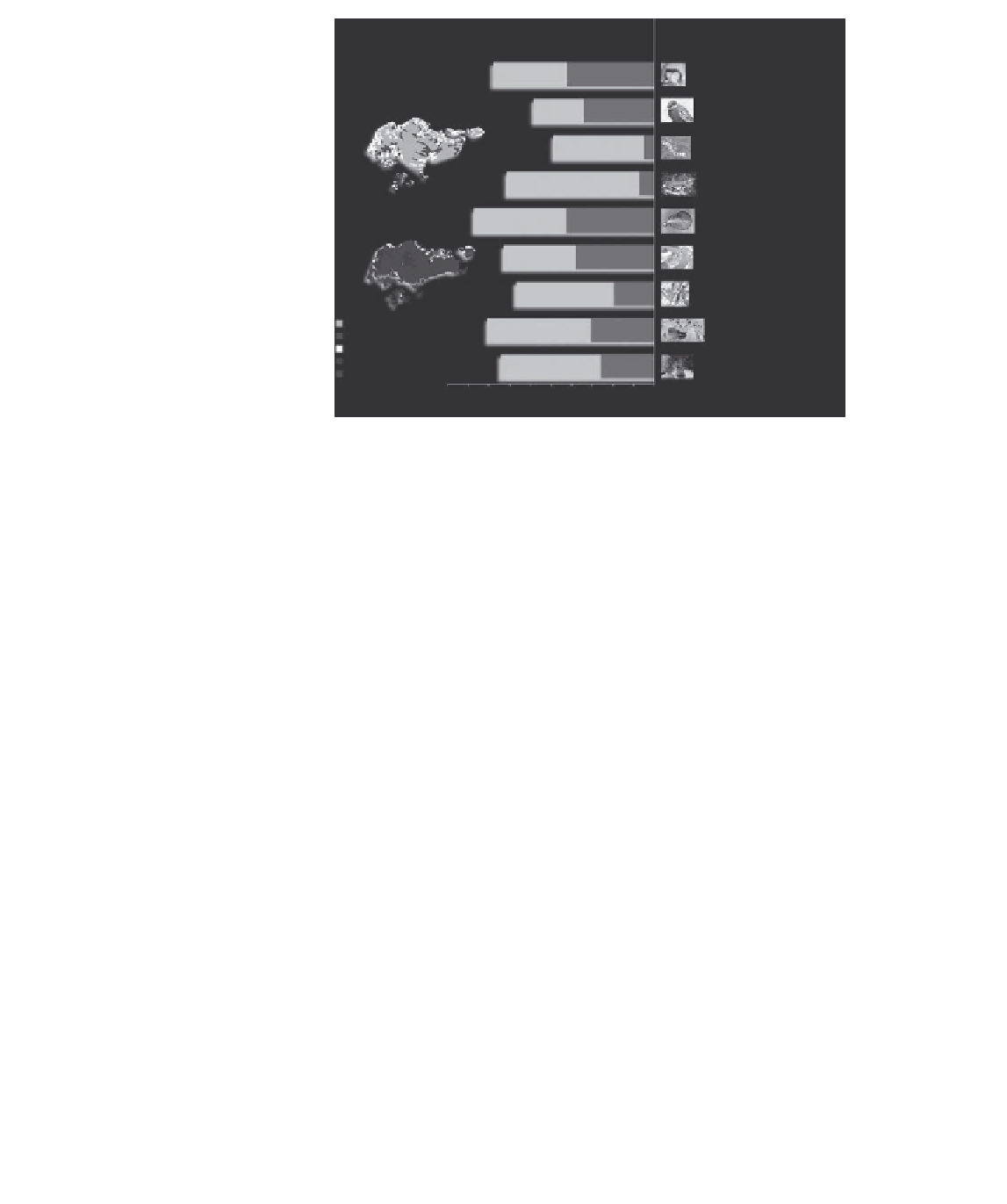

Fig. 1.5

Extinctions in

Singapore since the

early 1800s - green

(light) and blue (dark)

bars represent recorded

and inferred extinc-

tions, respectively.

(After Sodhi

et al., 2004.) (This

fi gure also reproduced

as color plate 1.5.)

Extinctions in Singapore

Mammals

Singapore in 1819

Birds

Reptiles

Amphibians

Fish

Singapore in 1990

Butterfiles

Phasmids

Primary rainforest

Decapod crustaceans

Freshwater swamp forest

Mangrove

Secondary forest

Urban and cultivated area

Plants

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Percentage of species extinct

produce new biomass (primary productivity), the rate at which dead organic matter

decomposes, and the extent to which nutrients are recycled from dead organic

matter back to living organisms. These processes are so fundamental that a substan-

tial change in any one will ramify throughout the food web.

Note, fi rst, that ecosystem properties are not invariably sensitive to a reduction

in biodiversity. It may be, for example, that different species carry out similar func-

tional roles and can 'cover for each other' should some be lost. In addition, some

species only contribute a little to productivity (or decomposition or nutrient cycling)

so their loss would barely register. Other species, however, contribute more

than their fair share - the extinction of one of these would be strongly felt (Hooper

et al., 2005).

Of most signifi cance is the question of whether species are 'complementary' in

the way they operate. If they are, then higher biodiversity will generally equate to

higher productivity (or decomposition rate, or nutrient recycling). Take, for example,

a set of grassland experiments carried out in Europe (Figure 1.6a). Plant biomass at

the end of the growing season was higher when each of three different functional

groups was represented (grasses, forbs (nongrass herbs) and nitrogen-fi xing

legumes). Similarly, the rate of breakdown of tree leaves that fall into streams is

higher when the richness of detritivorous insect species is higher (because they

'shred' and feed on the leaves in different ways) (Figure 1.6b). In these cases,

then, loss of species is likely to have a detectable impact on the way an ecosystem

functions. Managers need to beware loss of biodiversity, both for the sake of the

species concerned but also because of consequent changes to ecosystem

processes.

Search WWH ::

Custom Search