Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

The nature of many plant communities is strongly infl uenced by the local fi re

regime. A natural pattern of fi re intensity and frequency will have selected for plants

able to survive the fi res or with seeds keyed to germinate after the fi re goes out. The

great plains of North America evolved under the infl uence of relatively small-scale

fi res. The probability of fi re is greatest where a large biomass has accumulated

during a period without fi re. Recently burnt patches, with their dominant tallgrass

vegetation, tend to attract grazing animals (most notably the bison -

Bos bison

) that

reduce grass biomass, increase the amount of bare ground and shift the plant com-

munity towards nongrass herbaceous species. These changes reduce the likelihood

of fi re and of further grazing, because the animals now move to more recently burnt

areas. The patch then shifts back to a tallgrass successional stage, again increasing

the likelihood of fi re and of further grazing in future (Figure 8.3). Thus, small-scale

fi res and grazing together produce a shifting mosaic across the landscape, enhancing

heterogeneity and promoting biodiversity.

The traditional management practice when restoring these grasslands has been

to minimize patchy disturbance, leading to a reduction in patchiness of the succes-

sional mosaic. By contrast, Fuhlendorf and Engle (2004) recommend that manage-

ment should involve application of spatially discrete fi res together with free access

of grazing animals to a diversity of patches in a large landscape mosaic.

In contrast to the previous example (a shifting prairie mosaic), the goal of restora-

tion ecology is sometimes a relatively stable and homogeneous successional stage.

When the aim is to restore land previously under agriculture, managers need not

intervene if they are prepared to wait for natural succession to run its course. Thus,

abandoned rice fi elds in mountainous central Korea proceed from an annual grass

stage (

Alopecurus aequalis

), through forbs (

Aneilema keisak

), r ushes (

Juncus effusus

)

and willows (

Salix koriyanagi

), to reach w ithin 10 -50 years a species-rich and

stable alder woodland community (

Alnus japonica

). In this case the only active

intervention worth considering is the dismantling of artifi cial rice paddy levees

to allow the land to drain, and to accelerate, by a few years, the early stages of

succession (Lee et al., 2002).

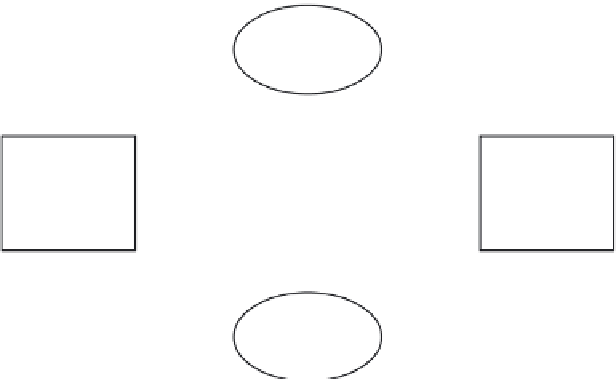

Fig. 8.3

Diagram of the

dynamics of a patch of

prairie in a shifting

mosaic landscape where

each patch experiences

similar but out-of-phase

dynamics. Ovals

represent the key

factors of fi re and

grazing while squares

represent the communi-

ties within a single

patch in relation to

time since fi re

disturbance. Solid

arrows indicate positive

(+) and negative (−)

feedbacks in which

plant community

structure is infl uencing

the probability of fi re

and grazing. Forbs are

nongrass herbaceous

species. (From

Fuhlendorf & Engle,

2004.)

Probability of

selection by

grazing animals

(+)

(-)

Recently burned,

currently grazed

Transitional

state

No fire for 3 years,

minimal grazing

<1

year

2-3

years

High production,

quality and

availability

of forage

High bare ground

and forbs and low

litter and standing

biomass

Accumulated litter

and standing

biomass of mostly

grasses

(-)

(+)

Probability

of fire

Search WWH ::

Custom Search