Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

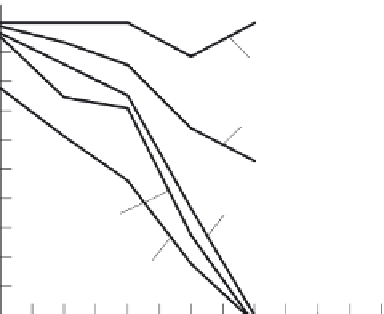

Long-term historical data sets often provide valuable insights. For example,

records have been kept for up to 70 years in the case of populations of bighorn sheep

(

Ovis canadensis

) in various desert areas in North America. By grouping these into

classes according to their population sizes at the commencement of record keeping,

it becomes clear that the smaller the population, the greater the risk of extinction

(Figure 5.3). Let's set an arbitrary defi nition of the necessary minimum viable

population, as conservation managers often do, as one that will give at least a 95%

probability of persistence for 100 years. Figure 5.3 can be explored to provide an

approximate answer. Populations of fewer than 50 individuals all went extinct

within 50 years while only 50% of populations of 51-100 sheep lasted for 50 years.

Evidently, for our minimum viable population we require a population with more

than 100 individuals: such populations demonstrated close to 100% success over

the maximum period studied of 70 years.

A similar analysis of long-term records of various species of birds on the Channel

Islands off the Californian coast indicates a minimum viable population of between

100 and 1000 pairs of birds (Thomas, 1990). These unusual data sets are available

because of the extraordinary interest people have in hunting (bighorn sheep) and

ornithology (Californian birds). Their value for conservation, however, is limited

because they deal with species that are generally not at risk. It is at our peril that

we use them to produce recommendations for management of endangered species.

There might be a temptation to report to a manager 'if you have a population of

more than 100 pairs of your bird species you are above the minimum viable thresh-

old'. But this would only be a (reasonably) safe recommendation if the species of

concern and those in the study had very similar life-history characteristics and if

the environmental regimes were similar, something that it would rarely be safe to

assume.

One fi nal point in the context of lessons for conservation managers from correla-

tional data concerns the species traits I discussed in Section 3.4.2. There you saw

that extinction risk is higher for large-bodied,

K

-selected species because of their

low reproductive rates. Thus, a link becomes clear between individual life-history

traits and population processes. The message for managers is clear - pay particular

attention to large-bodied species at risk.

Fig. 5.3

The percentage

of populations of

bighorn sheep that

persist over a 70-year

period is lower when

the initial population

size is smaller. (After

Berger, 1990.)

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

10

101+

51 -100

31-50

16 - 30

1-15

20

30

40

50

60

70

Time (years)

Search WWH ::

Custom Search