Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

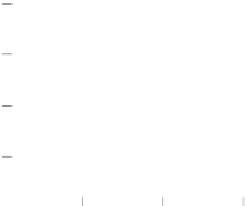

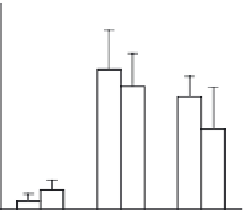

(a)

Chalinolobus morio

(b)

Vespadelus darlingtoni

(c)

Falsistrellus tasmaniensis

A

2.0

2.0

2.0

Logged

Unlogged

AB

1.5

1.5

A

1.5

A

A

1.0

1.0

1.0

A

AB

AB

A

AB

B

0.5

0.5

0.5

B

AB

B

B

B

B

B

0

0

0

Off-track

On-track

Riparian

Off-track

On-track

Riparian

Off-track

On-track

Riparian

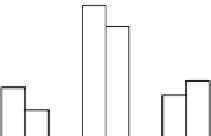

(d)

Vespadelus pumilus

(e)

Rhinolophus megaphyllus

2.0

2.0

A

A

A

1.5

1.5

A

A

AB

1.0

1.0

B

B

B

B

0.5

0.5

B

B

0

0

Off-track

On-track

Riparian

Off-track

On-track

Riparian

Fig. 4.11

Mean counts per night (

standard error) of fi ve bat species recorded at sites off track, along tracks and along

stream riparian corridors. Histograms that do not share the same letter are signifi cantly different. (a)-(d) Species considered

to be clutter-sensitive because of their morphology and behavior; (e) a clutter-tolerant species. (After Law & Chidel, 2002.)

+

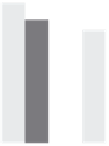

Fig. 4.12

Relationship

between total number

of recorded bat

movements and an

index of forest clutter

for all logged and

unlogged sites

combined. (After Law

& Chidel, 2002.)

3

2

1

0

-20

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

Index of forest clutter

clutter provided by regrowth in logged forest and the amount of understorey euca-

lypts in unlogged forest (Figure 4.12). This indicates that low bat activity away from

tracks and stream corridors was related to clutter.

While the opening up of forest tracks has clear benefi ts as feeding dispersal routes

for many species of bats, and the bat community recovers well within 15 years of

logging, it would be unsafe to conclude that logging is a blessing in disguise. Bird

Search WWH ::

Custom Search