Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

DIVISIONS IN JUDAISM

As a result of their history of dispersion

and exile, there are Jewish communities

in most countries of the world. Over

the centuries, different customs have

developed in the various

communities. The two

main strands, with their

own distinctive customs,

are the Sephardim, de-

scendants of Spanish

Jews expelled from

Spain in 1492, and

the Ashkenazim,

descendants of

Eastern European

Jews. In Western

Europe and the US,

some Jews adapted

their faith to the

conditions ofmodern

life, by such steps as improving the

status of women. This divided the faith

into Reform (modernizers) and

Orthodox (traditionalists), with Conser-

vative Jews somewhere in between.

Israeli Jews are frequently secular or

maintain only some ritual practices.

The ultra-Orthodox, or

haredim

, adhere

to an uncompromising form of Judaism,

living in separate communities.

Traditional Jewish life

is measured by the regular

weekly day of rest,

Shabbat

(from sundown Friday

to sundown Saturday), and a great many festivals

(see pp36-9)

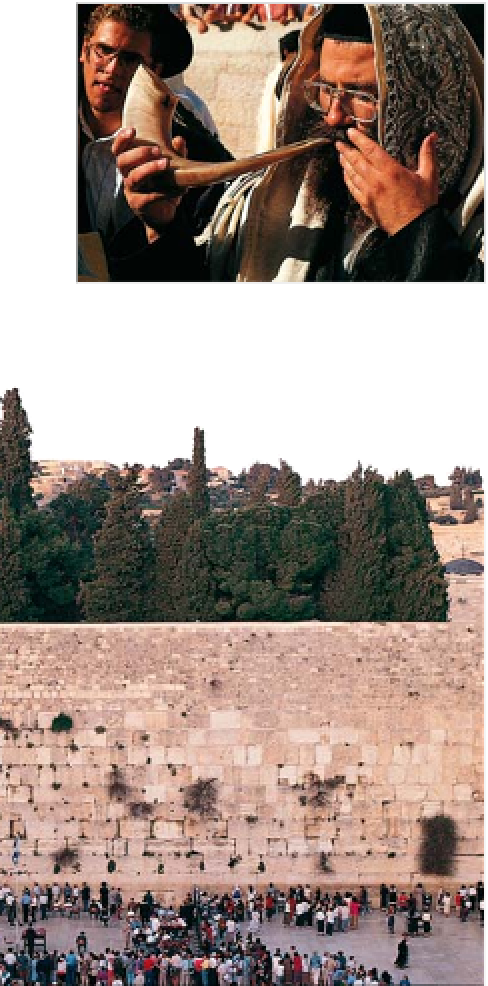

. The blowing of the

shofar

(a ram's horn

r

trumpet) marks

Rosh ha-Shanah

, the Jewish New Year.

Yemenite Jewess

in wedding dress

Ultra-Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem's Mea

Shearim district in distinctive black garb

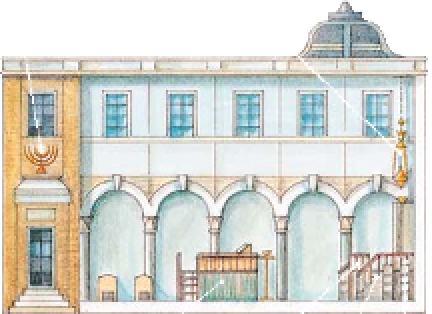

THE SYNAGOGUE

Synagogue architecture generally

reflects the architecture of the host

community, but with many standard

elements. There must be an ark,

symbolizing the Ark of the Coven-

ant, usually placed against the wall

facing Jerusalem. In front of the ark

hangs an eternal light

(ner tamid).

The liturgy is read from the lectern

at the

bimah

, the platform in front

of the ark. The congregation sits

around the hall, although in some

synagogues women are segregated.

Traditionally, a full service cannot

take place without a

minyan:

a

group of 10 men.

Eternal light, a symbol

of the divine presence

Menorah

Central platform for

reading of the law

Lectern

Bimah

Ark