Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

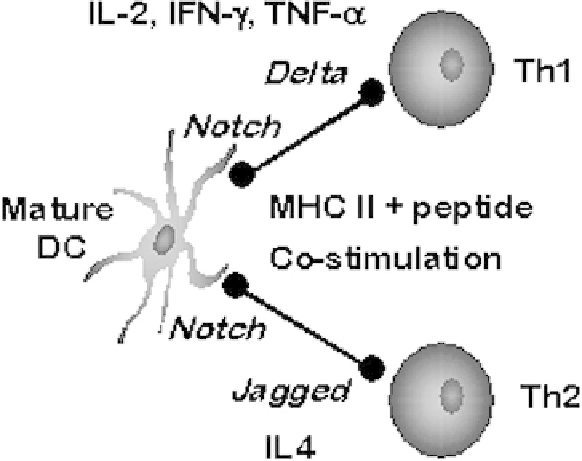

Fig. 1.

Signals provided by mature dendritic cells during the polarization of naive T cells.

molecules, changes in chemokine receptor expression to allow trafficking to

secondary lymphoid organs, and changes in cytokine and chemokine production to

influence T and B cells. Once in the local lymphoid tissue, DC and lymphocyte

interaction is far from simple.

Elegant experiments using two-photon microscopy of labeled DCs and T cells in

murine lymph nodes

in vivo

show that during the first 8 hours of antigen-matured DC

entry into the lymph node, mobile DCs and highly mobile T cells undergo short

encounters but with a progressive decrease in cell motility of both. During the next 12

hours T cells form long-lasting stable conjugates with the DCs and begin to secrete

specific cytokines. After 24 hours the T cells begin proliferating and resume rapid

migration and short DC contacts, although DCs do not resume motility (Mempel,

Henrickson, and Von Andrian 2004). The signals for prolonged DC/T-cell interaction are

not known but demonstrate that the function of DCs may also change within lymphoid

tissue. During the phase of prolonged interactions, the DC is likely to be providing the

signals required for MHC-restricted T-cell proliferation. These signals include antigenic

peptide loaded in MHC class I or II, costimulatory signals, cytokine signals (O'Garra

1998), and signals through the Notch/Delta/Jagged pathways (Maekawa, Tsukumo,

Chiba, Hirai, Hayashi, Okada, Kishihara, and Yasutomo 2003; Amsen, Blander, Lee,

Tanigaki, Honjo, and Flavell 2004). The strength, duration (Langenkamp, Messi,

Lanzavecchia, and Sallusto 2000), and combinatorial logic of these signals provide the

input for the T-cell to proliferate as a T

H

1 or T

H

2 polarized cell, thereby shaping the type

of immune response to the pathogen (Fig. 1). DCs could also provide the signals for T-

cell anergy or apoptosis in the absence of T-cell proliferation.