Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

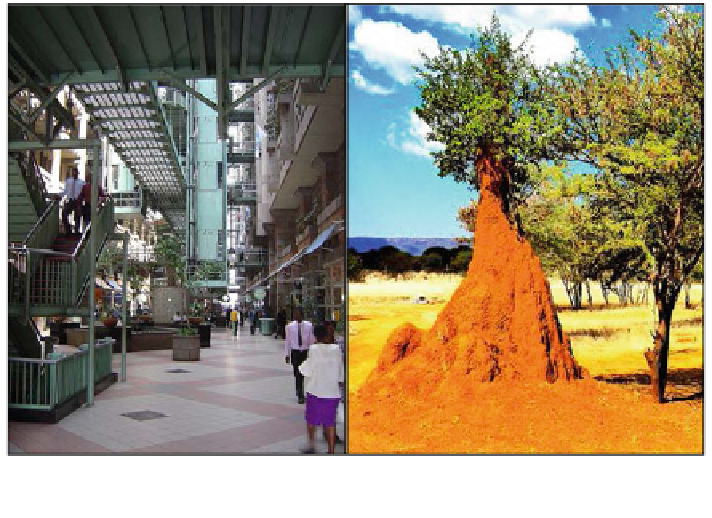

Fig. 4.2 Eastgate building in Harare, Zimbabwe (Photo By: G. Bembridge) and termite mound

in Africa (Photo By: D. Siu)

regulate temperature than was previously thought. This has led to suggestions that a

new generation of 'living' biomimetic buildings could utilise a more accurate

understanding of the termite mound as a multi-purpose extension of termite

physiology more analogous to the function of lungs (Turner and Soar 2008).

Although Eastgate could be considered to be a successful building in terms of

energy efficiency and GHG emissions reduction, it is an example of how architects

and designers are able to use a metaphor of how organisms work without a full

understanding of the science behind the mechanism. This demonstrates the

importance of working with ecologists and biologists to avoid 'bio-mythologically-

inspired' design (Pawlyn

2011

, p. 78).

An example of a building which attempts to take advantage of this new under-

standing of termite mounds (but perhaps does not fully exploit it) is the 2006 Davis

Alpine House by Wilkinson Eyre, Dewhurst MacFarlane and Atelier Ten located in

Kew Gardens, London, England (Fig.

4.3

). The building was designed to avoid

energy intensive refrigeration typically needed for the display of alpine plants, and

instead uses a stack effect to cool the interior passively, while essentially remaining a

glass house with high rates of air circulation (Pawlyn

2011

, pp. 87-88). A removable

shading sail is included in the design to prevent too much sunlight reaching the

plants. The stack effect is enhanced through the high internal space created by

the double arches, sequential apex venting as temperature increases, by vents at the

bottom of the glass structure, and through a Barossa termite inspired decoupled

thermal mass labyrinth below the building. The concrete block labyrinth is set

between a double concrete slab that also acts to resist the forces exerted by the

Search WWH ::

Custom Search