Geography Reference

In-Depth Information

and imagery (Warbington et al., 2002) because available

data vary in terms of nature, spatial resolution, spectral

characteristics, temporal frequency of acquisition, age of

database, homogeneity and cost (for example see Davis et

al., 2002 and Johansen et al., 2010 for recommendations

in image choice for riparian areas) (see Table 10.4).

We may distinguish, on the one hand, reach managers

with one site or a collection of sites that work at local

scale (i.e. at a reach length between a few hundred meters

and several kilometres) and, on the other hand, managers

that deal with the entire river network (thousands of

kilometres in length). The reach managers are directly in

charge of implementing and monitoring measurements

on the ground. The river basin managers are principally

in charge of political and strategical planning at net-

work scale. This distinction, though arbitrary in many

ways because the size of a given reach can also influence

technical choices (Geerling et al., 2009), is nevertheless

useful because the two different scales usually correspond

to different objectives. The reach-scale manager needs

more detailed information about species present on the

land, the area occupied by a given vegetation type, the

health condition of a given species, stand structure, exotic

species extension and changes of the riparian community

through time. Whereas at the network scale, managers

traditionally need more general indicators of corridor

structure (continuity, fragmentation, complexity) linked

to the distribution of riparian vegetation along the net-

work and human pressures. At such scale, all of these

indicators need to be systematically evaluated across all

contexts within the watershed (Cunningham et al., 2009;

Claggett et al., 2010).

The distinction between scales is also useful as the best

approach can depend on the scale used. For example

Johansen et al. (2007a), compared field measurements

to remotely-derived riparian zone characteristics such as

percentage canopy cover, organic litter on the ground,

canopy continuity, tree clearing, bank stability and flood

damage. They showed that field measurements are more

cost effective on a fine scale (1-200 km), whereas image

analysis is superior on a larger scale (200-2000 km).

At both scales, managers should always examine the

advantages and the limitations of images with respect to

their objectives and consider other approaches, notably

field assessment, as an alternative or a complement.

Table 10.3

Evaluation of the quality of the perception of a

circular object as a function of its dimension and of the spatial

resolution of the images.

Quality of the Perception

Very

Bad

Fair

Good

Very

Bad

Good

diameter of the object (in m)

2

4

8

16

24

area of the object (in pixels)

4

16

60

216

484

% of pure pixels

0

25

53

76

86

% of mixed pixels

100

75

47

24

14

Pixel size of the image

Diameter of the object

30 m

60

120

240

480

720

20 m

40

80

160

320

480

10 m

20

40

80

160

240

5 m

10

20

40

80

120

3m

6

12

24

48

72

1m

2

4

8

16

24

30 m

20 m

10 m

0

10 m

20 m

30 m

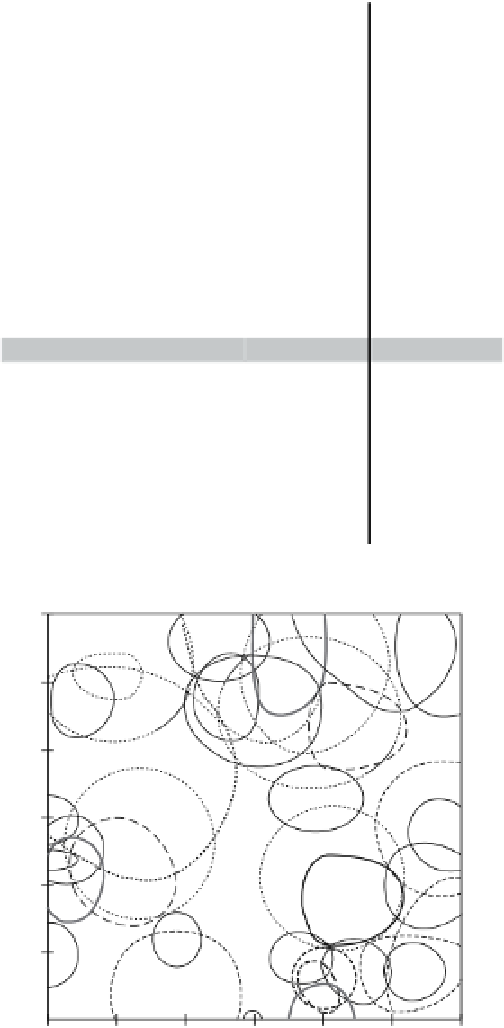

Figure 10.4

Example of the local diversity of riparian tree

canopies following field measurements within a plot equivalent

to one Spot or Landsat TM pixel.

10.4.1 Whichmanagers?Whichobjectives?

Whichapproach?

Remote imagery is used when there is a need for syn-

optic characterisation of an area, and hence an analysis

on a broad spatial scale. The scientific and/or manage-

ment objective is fundamental in choosing an approach

10.4.2 Limitationsof image-basedapproaches

With regards to riparian vegetation management, the

reach

scale

is

very

dominant

in

scientific

literature

Search WWH ::

Custom Search