Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

them by large waves. Sea walls also decay by physical, chemical and biological

weathering, a process that can be rapid on certain sandstones and limestones.

Construction of sea walls and similar structures on a particular sector of coast

to protect a building or a seaside resort is usually followed by continuing recession

on adjacent sectors, so that in due course the protected area becomes a promon-

tory. This has happened at the seaside resort of Mundesley, on the East Anglian

coast, which now protrudes between retreating cliffs of soft glacial drift, and at

Bray on the dune coast of north-eastern France. Eventually the flanks of such

promontories have to be stabilised artificially, and in due course the protected area

could become an island.

Another response to beach erosion has been to introduce structures designed to

retain a beach that protects a coastline from strong wave action. A breakwater built

out from the coastline can intercept longshore drift in order to form a higher and

wider beach sector updrift for some distance along the shore. The prograded sector

becomes triangular and extends towards the outer end of the breakwater.

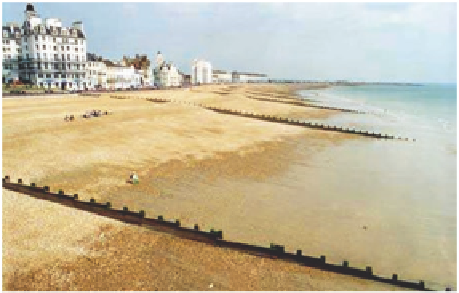

Multiple groynes (groyne fields), built of timber, masonry, sheet metal, boul-

ders or concrete, have been inserted on some coasts, especially at seaside resorts

such as Eastbourne in Sussex (Fig.

3.2

), with the aim of retaining longshore drift

and so protecting the coastline. Beach sand and gravel are intercepted in the inter-

vening compartments, and accumulate until sediment spills over or round each

groyne. Sometimes a larger terminal groyne is built at the downdrift end (Fig.

3.3

).

As sediment drifting along the shore is trapped by the groynes the supply to

downdrift beaches is reduced, and erosion is thus transferred along the coast.

There is then a temptation to extend the groyne field: there are sectors of the coast-

line of England and Wales that now have multiple groynes for several miles.

Groynes have been successful in retaining beaches on some coasts, particu-

larly where wave energy is generally low (Fig.

3.4

), but storm waves may break

in such a way as to withdraw sand or shingle seaward from beach compartments

to the nearshore sea floor. Some of the withdrawn beach sediment may be returned

during subsequent periods of calmer weather, but it is possible that longshore

drift will carry it away along the nearshore zone, leaving the beach compartment

between the groynes depleted (Fig.

3.5

).

Fig. 3.2

Groynes defining

beach compartments at

Eastbourne on the Sussex

coast, England. © Geostudies