Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

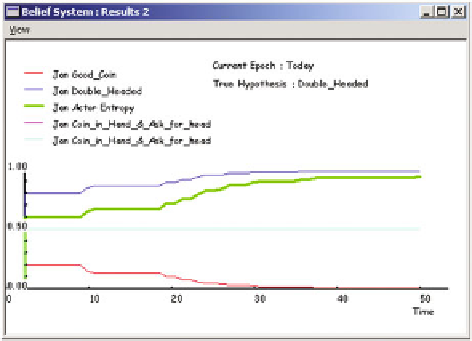

Fig. 6.3

Agent 'Jan' starts

with a positive bias

Agent 'Jan' in Fig.

6.2

believes 0.2 that the coin is good and 0.8 that it is double

headed. The result is a steady increase in confidence towards the final conclusion

that it is a 'fact'.

The flat centre plotlines in these figures indicate that in all cases the actions

'Ask for head' and 'Ask for tail' remain equally likely (probability of 0.5). From an

information point of view the options are about the same, no matter what the agent's

belief might be. This is due to the simplicity of the situation. In more complex cases

a genuine bias between the actions will become apparent as belief changes (see

Gooding and Addis

2004

) (Fig.

6.3

).

6.11

Other Examples

We have also run this simulation using an extension of Wason's four-card problem

(Wason

1960

; Wason and Shapiro

1971

). In the original task sets of four cards are

displayed, two showing integers and two characters (e.g., A, D, 4, 7). The subject

is asked to turn a card (or cards) to show that the rule 'An even number implies

a vowel on the other side'. Wason was testing whether subjects reasoned so as to

falsify the rule (so the expected action is to turn an even number and just one other

card (Johnson-Laird and Wason

1977

)). We adapt this problem by providing our

agents with 100 cards and, in some scenarios, access to other agents. Each card

represents a possible experiment, although there are only four distinct choices (to

turn a vowel, a consonant, an odd or an even). The entropy-driven mixed strategy (see

Evaluation Actions—Choosing Actions) implies that the rule should be discovered

with a minimum number of turns.

This scenario allows for ten possible logically distinct rules (or hypotheses; see

Addis and Gooding

1999

, pp. 23-24). The simulated agents 'home in' on the correct

rule within ten or so moves (see Fig.

6.4

). They also correctly eliminate the redundant