Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

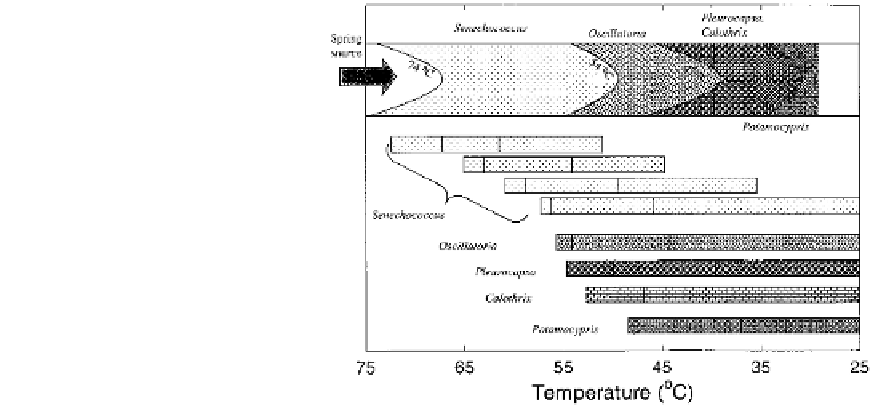

FIGURE 15.4

Distribution of cyanobacterial genera and strains and the grazing ostracod

Potamocypris

in Hunter's Hot Spring, Oregon. Dominant species on top with distribution lim-

its. Bars give temperature ranges of each organism, with gray portion of each bar representing

the temperature range for optimum growth (adapted from Wickstrom and Castenholz, 1985).

COLD HABITATS

Cold habitats include ice, snow, and polar lakes. These habitats can be

present for part of the year in temperate areas or much of the year in po-

lar or high-altitude regions. Organisms that live in these habitats have to be

able to function at low temperatures. There are two general groups of or-

ganisms. The first group of organisms in low-temperature habitats are also

found in more moderate habitats, where they have much higher rates of me-

tabolism. The second group of organisms are

psychrophilic,

meaning they

require cold temperatures (generally below 5°C) to grow and/or reproduce.

The psychrophiles are more rare but more interesting physiologically.

Only recently has the attention of some biotechnology researchers been

focused on psychrophilic organisms. Such organisms produce proteins that

are active at low temperatures. These compounds could be useful in cold

food preparation and in detergents for washing in cold water (Russell and

Hamamoto, 1998).

The lakes in the dry valleys of Antarctica (Fig. 15.1) provide a perma-

nently cold habitat. These lakes have several meters of ice cover year-round,

so they receive very low levels of light. The primary producers (planktonic al-

gae) found in the lakes are adapted to compete for light (steep

and low

compensation points for the photosynthesis-irradiance curves; see Chapter

11). Some primary producers are able to consume small particles as well as

photosynthesize, and this may allow them to survive the long winter with no

light (Roberts and Laybourn-Parry, 1999). The communities are simple, with

no fish or large invertebrates. Some of the lakes have warmer regions fed by

saline, geothermally heated warm springs (Fig. 15.5). These warmer regions

are anoxic, have high nutrients (Green

et al.,

1993), and have an enhanced

population of primary producers located at the chemocline (Fig. 15.5B).

Search WWH ::

Custom Search