Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

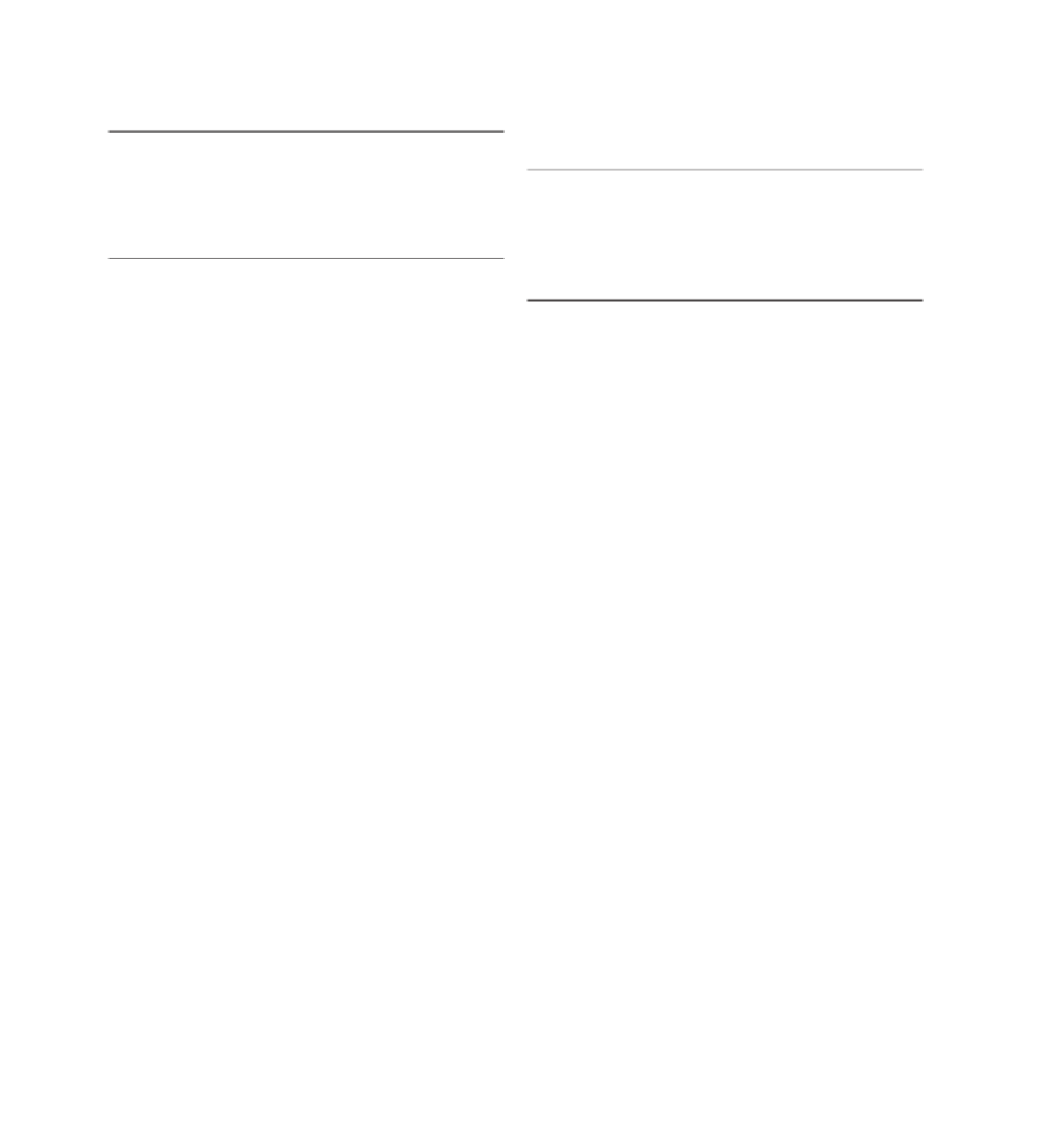

Table 12.3

Effect of two cropping sequences on downy

brome plant density.

Table 12.4

Effect of underseeded sweetclover in 1993 on

weed growth during fallow in 1994 and spring wheat yield

in 1995.

Continuous Winter

Wheat (plants m

−2

)

Winter Wheat-Canola

(plants m

−2

)

Year

Weed Biomass

(September 1994)

Wheat Yield

(1995)

1988

30

28

Crop Treatment

(g m

−2

)

(kg ha

−1

)

1989

54

25

1990

190

35

Field peas (1993)

446

2,970

1991

400

70

Mustard (1993)

156

2,160

1992

920

38

Field peas

sweetclover

(1993-1994)

+

14

3,750

1993

740

40

Mustard

sweetclover

(1993-1994)

+

3

3,520

Source:

Adapted from Blackshaw (1994a).

Source:

Adapted from Blackshaw et al. (2001b).

could effectively be controlled through use of

diverse crop rotations.

Fallow is often included in rotation with wheat

in the semiarid Great Plains of North America.

Fallow can effectively reduce weed populations

(Blackshaw et al., 2001a; Anderson 2003), but it

can negatively affect soil quality and expose the

soil to erosion. Research has examined the useful-

ness of cover crops and green manure crops as

partial fallow replacements. Moyer et al. (2000)

documented that a winter rye (

Secale cereale

L.)

cover crop planted after harvest of summer crops

suppressed weed growth in the fall and early

spring. Winter rye residue, after terminating the

crop at heading in June, continued to suppress

weeds for the remainder of the fallow period,

likely due to combined physical and allelopathic

effects (Teasdale 1996; Weston 1996). Another

study found that underseeded biennial sweetclo-

ver [

Melilotus offi cinalis

(L.) Lam] reduced weed

establishment after harvest and in the following

spring before being terminated at the 90% bloom

stage in late June (Blackshaw et al., 2001b). Sweet-

clover residue provided excellent weed suppres-

sion throughout the remaining portion of the

fallow year. Wheat yield in the subsequent pro-

duction year was higher due to fewer weeds and

greater nitrogen availability from sweetclover

nitrogen fi xation (Table 12.4).

Diverse crops grown in rotation with wheat

allow for greater herbicide choice over years and

may avoid continuous use of the same herbicide

with inadvertent selection for weed resistance.

Additionally, crop diversity encourages opera-

tional diversity that, in turn, can facilitate

improved weed management. Different crops are

naturally planted and harvested at different times

of the year. If suffi cient differences exist in ger-

mination requirements between the rotational

crop and potential weed species, then seeding

date can be manipulated to benefi t the crop. Early

sown spring crops may out-compete weeds that

require warmer soil temperatures for germina-

tion. For example, densities of the C

4

species

green foxtail have declined in early planted spring

crops such as canola or fi eld pea (

Pisum sativum

L.) in zero-tillage systems that often have lower

soil temperatures (Blackshaw 2005). Conversely,

delayed seeding can be used to manage early

spring germinating weeds such as kochia [

Kochia

scoparia

(L.) Schrad.]. Alternating seeding dates

over years is a desired weed management practice

and one that farmers should try to implement.

Wheat cultivars can vary considerably in their

competitiveness with weeds (Hucl 1998; Lemerle

et al., 2001). Winter wheat cultivars have been

identifi ed that differ in their competitive ability

with downy brome (Blackshaw 1994a). Wheat

yield reductions caused by downy brome varied

by as much as 30% depending on the cultivar

grown (Table 12.5). Tall (non-semidwarf) culti-

vars (90-110 cm) had a height advantage over

downy brome (70 cm) and cultivars with a spread-

ing growth habit provided better interrow shading

of downy brome. Increased competitive ability of

wheat, or crops in general, has been associated