Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

extraction [

] indicate that the

degree of resorption is a function of gender

and age. Further, because the tooth extraction

site involves both soft and hard tissues, it

represents a unique situation for evaluating

bone healing and regenerative devices and

molecules.

The healing of an extraction site is affected

by events in two regions of the healing site: the

socket space where the root was located and the

residual alveolar bone that supported the tooth.

Histologic evaluation of the healing tooth

socket has shown that the resultant bone for-

mation fi lls most of the space. Initial clot for-

mation is followed by cellular infi ltration with

the formation of highly vascularized granula-

tion tissue. Osteoid becomes evident

30

,

32

,

48

,

69

7

to

14

days after extraction, and by

days the major-

ity of the socket space has become fi lled with

mineralized tissue [

30

]. Even though a corti-

cal “bridge” covers the coronal aspect of the

socket space, the newly formed alveolar bone

within the socket continues to remodel, with an

increasing percentage of marrow space devel-

oping over time. Furthermore, residual tissues

from the disrupted periodontal ligament fol-

lowing tooth extraction appear to have little

effect on this healing process [

1

,

12

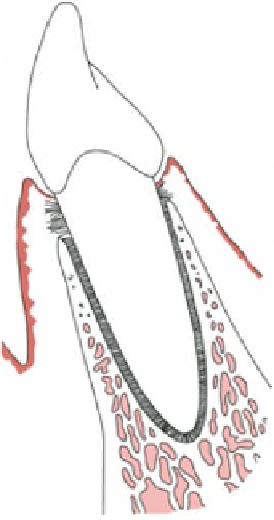

Figure 9.1.

Schematic cross-sectional representation of the

tooth-supporting tissues of the periodontium.

].

The second region involved in the extraction

site is the retained alveolar bone that previ-

ously supported the tooth. Numerous studies

have demonstrated that signifi cant dimen-

sional losses, involving as much as

12

through the mandible, innervating and supply-

ing blood to the lips and face. As a result, only

a limited amount of vertical bone is left. When

teeth are lost from the maxilla, the sinuses

located above the roots of the back teeth enlarge

and thus come close to the remaining alveolar

ridge crest. This also weakens denture

support.

Tooth replacement has been revolutionized

by dental implant therapy, which over the last

three decades has become the optimal form of

tooth replacement [

% of the

buccolingual dimension of the alveolar ridge,

occur within the fi rst

50

months of healing.

This dimensional change can amount to

3

to

4

5

to

7

mm of horizontal bone loss and can have a

great impact on subsequent dental implant

therapy [

]. The patterns of resorp-

tion of the residual bone are unique, with

greater resorption occurring along the facial

than the lingual aspect of the extraction site

[

3

,

13

,

49

,

56

]. Implants are endosse-

ous titanium screw devices that, after careful

preparation of the bone, are screwed into the

bone tissue to a depth that ranges from

15

12

mm. The procedure is successful in more than

90

8

to

]. This may be because the facial alveolar wall

is thinner than the lingual aspect and may

therefore be more susceptible to losses of ridge

height and width that occur in the course of

bone remodeling during the healing process.

Recent attempts to modify the relatively

extensive resorption of bone that occurs after

tooth extraction have included placement of a

dental implant into the extraction site immedi-

ately after tooth removal and bone grafting of

the sites following the principles of guided

bone regeneration (GBR), as will be discussed.

2

% of cases. Moreover, a small number of

implants can replace many teeth. Implant

therapy depends on bone dimensions adequate

to allow placing the implant in the bone. Fol-

lowing tooth extraction, alveolar bone under-

goes remodeling typical of tissue injury and

infl ammation. Some systemic interactions may

impact upon the remodeling process. Studies of

the relationship between bone mineral density

(BMD) and alveolar ridge resorption following