Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

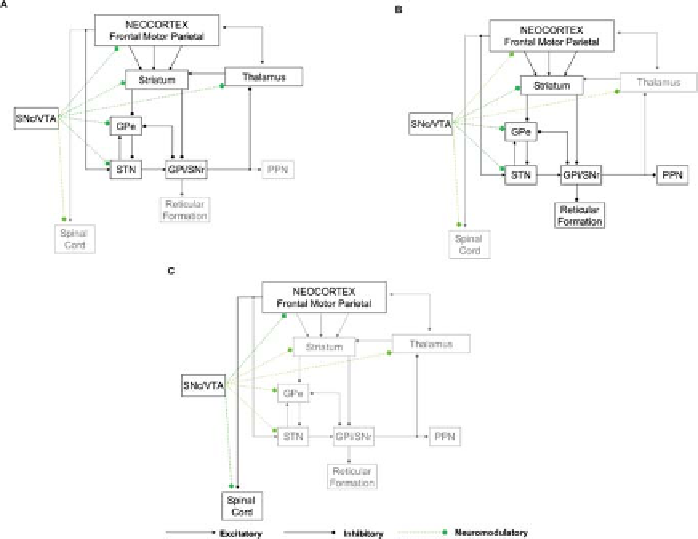

Fig. 11.1: Brain anatomical pathways in Parkinson's disease. (

A

) Pathways from

the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) and the ventral tegmental area (VTA)

to the striatum and from there to the thalamic nuclei and the frontal cortex through

the substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNr) and the globus pallidus internal segment

(GPi). (

B

) Pathway from the SNc and the VTA to the striatum and from there to

the brainstem through the SNr and GPi. (

C

) Pathway from the SNc/VTA to corti-

cal areas such as the supplementary motor area (SMA), the parietal cortex, and the

primary motor cortex (M1), and from there to the spinal cord.

the SNc/VTA to cortical areas such as the supplementary motor area (SMA), the

parietal cortex, and the primary motor cortex (M1), and from there to the spinal cord.

The most popular view is that cortical motor centers are inadequately activated

by excitatory circuits passing through the basal ganglia (BG) [1]. As a result, inad-

equate facilitation is provided to the otherwise normally functioning motor cortical

and spinal cord neuronal pools and hence movements are small and weak [1]. Re-

cently, a new view has been introduced by the modeling studies of Cutsuridis and

Perantonis [21] and Cutsuridis [18, 19, 20]. According to this view, the observed de-

layed movement initiation and execution in PD is due to altered activity of motor

cortical and spinal cord centers because of disruptions to their input from the basal

ganglia structures and to their dopamine (DA) modulation. The main hypothesis

is that depletion of DA modulation from the SNc disrupts, via several pathways,