Geology Reference

In-Depth Information

Climate

Hautes-

Roches

Pertuis

Savagnières

Gorges

de Court

General climate models for the Late Jurassic have

been developed by Oschmann (1990), Frakes

et al

.

(1992), Sellwood & Valdez (1997), or Abbink

et al

.

(2001). These models, however, do not consider

short-term climate variations. Orbital cyclicity

causes changes in the total amount of insolation

and in its seasonal distribution, which then result

in latitudinal shifting of atmospheric circulation

cells and concomitant changes in seasonality,

rainfall pattern, oceanic circulation and sea-sur-

face temperatures (Matthews & Perlmutter, 1994).

In the sections studied, siliciclastics are in many

cases concentrated around small-scale sequence

boundaries and associated with plant material

(Fig. 6). This implies that during sea-level fall cli-

mate in the hinterland was rather humid, increas-

ing the terrigenous runoff and allowing vegetation

growth. Coral reefs and ooid shoals are situated

preferentially in the trangressive parts of small-

scale and medium-scale sequences in the absence

of siliciclastics, suggesting a rather dry and warm

climate. However, there are many exceptions to

these trends, so that humid-dry changes can be

considered as only one controlling factor among

several others. There is no evidence for arid con-

ditions as no evaporites have been observed in

the sections studied. It is interesting to note that

in Upper Oxfordian sections in Spain, in a more

southern palaeolatitudinal position, the siliciclas-

tics are preferentially associated with maximum

fl ooding in small-scale sequences (Pittet & Strasser,

1998). This implies that rainfall there occurred

during rising sea-level and places the Spanish sec-

tions in a different palaeoclimatic zone than those

in the Swiss Jura.

The estimation of water temperature is diffi cult.

Based on

Vorbourg

Sequence boundary

seasonally wet ?

(d)

Maximum flooding

dry climate

(c)

Sequence

boundary

(b)

Sequence boundary

humid climate

(a)

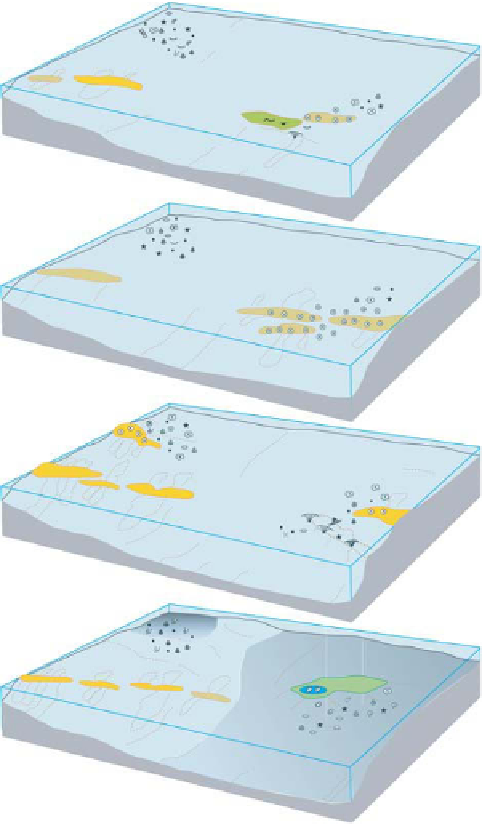

Fig. 10.

Sketches of depositional environments along the

time lines indicated in Fig. 9. Platform morphology has

been reconstructed to be compatible with the evolution of

facies and sequences observed in the sections studied. For

discussion refer to text. No palinspastic correction has been

applied: the distances between the sections may therefore

be somewhat different from Late Jurassic times but their

relative positions have not changed.

18

O analyses on modifi ed whole rock,

Plunkett (1997) derived an average palaeotemper-

ature of 26-27°C for samples in the Vorbourg and

Gorges de Court sections. The isotopic variations

within individual depositional sequences, how-

ever, are too weak to be interpreted confi dently as

high-frequency temperature changes.

δ

south, whereas lagoons formed in the depressions

towards the north (Fig. 10). The relief created by

tectonics therefore contributed signifi cantly to

the general facies distribution. Furthermore, the

irregular distribution of siliciclastics (Fig. 6) can

be explained by depressions, which were created

by differential subsidence and served as con-

duits (Pittet, 1996; Hug, 2003). The preferential

growth of reefs and the initiation of ooid shoals on

tectonic highs further enhanced the relief.

Ecology

The most conspicuous carbonate-producing eco-

systems in the sections studied are coral patch

reefs. They occur in different stratigraphic positions

and the individual reef bodies never lived longer

than the duration of an elementary sequence,

i.e. 20 kyr (Figs 6 and 9). The Oxfordian reefs