Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

these changes indefinitely. Of particular concern are

flood control dams that produce controlled discharges

to an estuary rather than relatively short but massive

discharge during high-flow periods. Dams operated to

impound water for water supplies during low-flow

periods may drastically alter the pattern of freshwater

flow to an estuary, and although the annual discharge

may remain the same, seasonal changes may have sig-

nificant impact on the estuary salinity distribution and

its biota.

Well mixed

Stratified

Partially

mixed

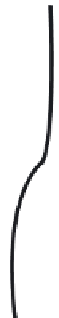

Stratification Classification of Estuaries.

Stratiication

is most often used for classifying estuaries influenced by

tides and freshwater inflows. Three stratification classes

of estuaries are: (1) highly stratified estuaries, (2) par-

tially mixed estuaries, and (3) vertically homogeneous

estuaries. The primary parameter used to classify the

stratification potential of estuaries is the

Richardson

number

, Ri, which measures the ratio of buoyancy to

shear forces and for estuaries can be put in the form

Salinity

Figure 9.16.

Salinity gradient in an estuary.

Source

: National

Oceanography Centre, Southhampton, UK (2005).

1.5757 10

×

5

6.6423 10

×

7

c

=

exp

−

139.34

+

−

o

=

∆ρ

ρ

gQ

WU

3

T

T

2

f

Ri

a

a

(9.82)

(9.81)

10

8.6219 10

11

4

T

a

1.2438 10

×

×

t

+

−

3

T

a

where Δ

ρ

is the difference between freshwater and sea-

water density, typically 25 kg/m

3

;

ρ

is the reference

density, typically 1000 kg/m

3

;

g

is gravity (m/s

2

),

Q

f

is the

freshwater inflow (m

3

/s);

W

is the width of the estuary

(m); and

U

t

is the mean tidal velocity (m/s). If Ri is large

(>0.8), the estuary is expected to be strongly stratified

and dominated by density currents, and if Ri is small

(<0.08), the estuary is expected to be well mixed. Transi-

tion from a well-mixed to a strongly mixed estuary

occurs in the range 0.08 < Ri < 0.8. The stratification

classifications of several estuaries in the United States

are shown in Table 9.10.

It is apparent from Equation (9.80) that as the salinity

increases, the saturation concentration of DO decreases.

Salinity distribution has a dominant effect on mixing

in estuaries. Highly stratified (stable) estuaries offer sig-

nificant resistance to vertical mixing. Typical (vertical)

salinity profiles in estuaries are illustrated in Figure 9.16.

In stratified estuaries, there is a significant vertical varia-

tion in salinity, with a relatively uniform top layer over

a relatively uniform bottom layer, with a sharp salinity

gradient in between. In well-mixed estuaries, there is a

relatively small vertical variation in salinity, and par-

tially mixed estuaries have vertical salinity distributions

somewhere in between those of stratified and well-

mixed estuaries.

The two most important sources of freshwater to

an estuary are inflow from streams and rainfall, with

stream flow typically representing the greater contribu-

tion. The location of the salinity gradient in a river-

controlled estuary is to a large extent a function of

stream flow, and the location of the isoconcentration

lines may change considerably depending on whether

stream low is high or low. This in turn may affect the

biology of the estuary, resulting in population shifts

as biological species adjust to changes in salinity.

Most estuarine species are adapted to survive tempo-

rary changes in salinity either by migration or some

other mechanism (e.g., mussels can close their shells).

However, many estuarine organisms cannot withstand

9.3.4 Dissolved Oxygen: The Estuary

Streeter-Phelps Model

The Streeter-Phelps model can be adapted for applica-

tion to river estuaries, in which case the governing equa-

tions for DO and BOD are given by

V

dD

dx

K

d D

dx

2

(9.83)

=

+

k L k D

−

L

d

a

2

V

dL

dx

K

d L

dx

2

(9.84)

=

−

k L

L

r

2

where

V

is the longitudinal mean velocity (lT

−1

),

D

is

the oxygen deficit (l),

x

is the along-stream coordinate

(l),

K

l

is the longitudinal dispersion coefficient (l

2

T

−1

),

Search WWH ::

Custom Search