Biomedical Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

The GI tract is one of the largest immunological organs of the body, containing more lympho-

cytes and plasma cells than the spleen, bone marrow, and lymph node. Ingestion is considered as an

exogenous source of exposure, primarily through the mouth in the workplace. Alternatively, the NPs

can be directly ingested via water, ingestion, food, drugs, or drug-delivery systems. In addition, NPs

cleared from the respiratory tract via the mucociliary escalator can be subsequently ingested into

the GI tract. Thus, GI tract is considered as an important target for NPs exposure (Zhao et al. 2010).

13.2.1 e

xposure

s

ources

of

Np

s

Endogenous sources of NPs in the GI tract are derived from intestinal calcium and phosphate secre-

tion (Lomer et al. 2004). Exogenous sources are particles from food (such as colorants, titanium

oxide), pharmaceuticals, water or cosmetics (toothpaste, lipstick) (Lomer et al. 2004), dental pros-

thesis debris (Ballestri et al. 2001), and inhaled particles (Takenaka et al. 2001). The dietary con-

sumption of NPs in developed countries is estimated around 1012 particles/person/day (Oberdörster

2004). They mainly consist of TiO

2

and mixed silicates. The use of specific products, such as salad

dressing, containing an NP, such as a TiO

2

whitening agent, can lead to an increase of the daily

average intake by more than 40-fold (Oberdörster 2004). These NPs do not degrade in time and

accumulate in macrophages. A database of foods and drugs containing NPs can be found in Lomer

et al. (2004). A portion of the particles cleared by the mucociliary escalator can be subsequently

ingested into the GI tract. Also, a small fraction of inhaled NPs was found to pass into the GI tract

(Takenaka et al. 2001).

13.2.2 s

Ize

-

aNd

c

harge

-d

epeNdeNt

u

ptake

of

Np

s

The GI tract is a complex barrier-exchange system and is the most important route for macromol-

ecules to enter the body. The epithelium of the small and large intestines is in close contact with

ingested material, which is absorbed by the villi (Figure 13.1). The uptake of NPs and microparti-

cles has been the focus of many investigations, the earliest dating from the mid-seventeenth century,

while the entire issues of scientific journals have been devoted to the subject more recently (Hussain

et al. 2001). The extent of particle absorption in the GI tract is affected by size, surface chemistry

and charge, length of administration, and dose (Hoet et al. 2004).

The absorption of particles in the GI tract depends on their size, and the uptake diminishing for

larger particles (Jani et al. 1990). A study of polystyrene particles with sizes between 50 nm and

3 μm indicated that the uptake decreases with increasing particle sizes from 6.6% for 50 nm, 5.8%

for 100 nm NPs, 0.8% for 1 μm, to 0% for 3 μm particles. The time required for NPs to cross the

colonic mucus layer depends on the particle size, with smaller particles crossing faster than larger

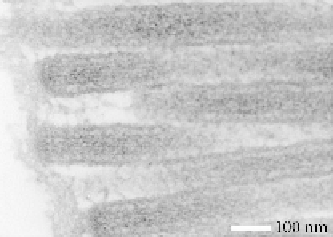

FIGURE 13.1

TEM image of a thin section cut through a segment of human small intestine epithelial cell. One

notices densely packed microvilli, each microvillus being approximately 1 μm long and 100 nm in diameter.

(The image is courtesy of Chuck Daghlian, Louisa Howard, Katherine Connollly.)