Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

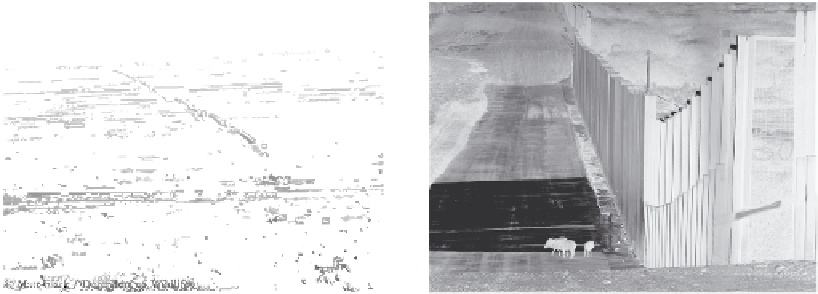

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 9.4

The 660-mile-long border fence between Mexico and the United States is a barrier that disrupts animal

movement and fragments habitat. Picture (a) indicates the extent to which the border fence can bisect des-

ert ecosystems, while picture (b) illustrates the physical barrier the fence can be to large wildlife species.

(From Clark, M., Defenders of Wildlife; San Pedro River Valley fragmented by border wall, previously

unpublished.) (Courtesy of Matt Clark.)

Some organisms can withstand and may even benefit from modest levels of habitat frag-

mentation. For example, prey populations can expand with increased availability of water

in areas with low density housing or the construction of golf courses and greenbelts.

21

The

negative consequences of habitat fragmentation in these settings may be partially offset

by the increased availability of resources required by the native wildlife. In the Sonoran

Desert near Tucson, coyotes benefited from living in an area near Saguaro National Park

bordering suburban areas. Rodents were captured more frequently in suburban areas

than rural ones, but coyotes apparently substituted human-related foods (dog food, bread,

fruits, vegetables, table scraps) for rodents and other foods in some areas.

27

9.4.1

Habitat Alteration

Perhaps, the least obvious and more subtle of anthropogenic changes to habitats of the

Southwest have had the most far-reaching consequences for wildlife: habitat alteration in

the form of introduced species. Urbanization is invariably associated with the introduction

of any number of plants and animals including dogs, cats, pigs, horses, and various birds

to adjacent habitat resulting in further habitat alteration. Many of these domestic animals,

like the cats described earlier, have important effects on native wildlife, but those associated

with livestock have received the most attention. Cattle and sheep range far from urban

and other obviously developed areas and affect wildlife in significant ways (Figure 9.5).

Livestock grazing has led to the establishment of introduced plant species and has been

implicated in the conversion of grassland to shrubland in many arid areas of Arizona

and New Mexico (Figure 9.6). The ability of cattle to modify habitats has even been used

to reduce introduced grasses in some highly disturbed communities, such as the historic

desert shrublands of the San Joaquin Valley of California.

28

In southwestern New Mexico,

degradation of grassland and increases in shrubland because overgrazing has favored

range expansion of the desert grassland whiptail lizard while negatively affecting the

grassland specialist Arizona striped whiptail, although this has yet to occur in Arizona.

29

Livestock ranching and agricultural activities are intimately associated with the

construction of impoundments, lowering water tables and draining of springs; all of these

Search WWH ::

Custom Search