Travel Reference

In-Depth Information

accounted for 90% of all flows. The intra-eastern

bloc exchanges were shaped by ideological

priorities. These were to 'promote international

friendship' and 'a better understanding of

brother nations'. The real world was rather

different. After the Solidarity movement had

secured a position of political influence in

Poland in 1980, the Czechoslovak authorities

imposed complex barriers on travel to that

country, and the need to develop a 'better

understanding of a brother nation' was set

aside. Instead, a system of special permissions

was introduced for trips to Poland, so that after

1982, with martial law imposed in Poland,

such tourism exchanges were severely reduced.

Tourist flows with the former USSR were

heavily restricted. While there was no problem

buying a package trip, individual trips were

restricted to strictly prescribed travel routes

between borders and Black Sea coastal resorts.

There were a number of areas closed to foreign-

ers. Cross-border exchange between Slovakia

and Ukraine was prohibited (MVSR, 2004b).

Local inhabitants wishing to visit their relatives

on the other side of the border (sometimes no

more than a few hundred metres away), had to

arrange visas in Prague and Moscow.

Hence, the most significant developments

in international travel after 1989 were the

removal of passport and visa formalities. In 1990

the former Czechoslovakia signed non-visa tourist

exchange agreements with 18 countries, includ-

ing Austria, Germany and Italy. Five other

countries followed suit in 1991, and by 1992

agreements were in place with most European

states. Restrictions on travel to Poland were also

lifted and travel to Ukraine liberalized. In 1993

Slovakia signed the Association Agreement with

the EU, which was another major impetus for

liberalized travel.

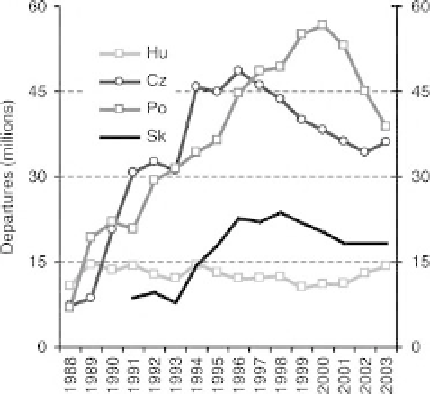

Liberalization of travel was reflected in

huge increases in the scale of international tour-

ist flows (Figs 8.2 and 8.3). All four ECE coun-

tries (the Czech and Slovak Republics, Hungary

and Poland) have experienced broadly similar

trends in inbound tourism, with a period of

rapid expansion after 1989 being followed by

decline or static numbers. Whereas 29.6m for-

eign visitors came to Czechoslovakia in 1989,

by 1996 this number had leapt to 109.4m

visitors to the Czech Republic (CNTO, 2004)

and 33.1mn to Slovakia (ŠÚSR, 1991-2005).

Fig. 8.2.

Foreign visitors at frontiers in ECE,

1988-2003. Sources: ŠÚSR, 1991-2005; HNTO,

2003; CNTO, 2004; PIT, 2004.

Fig. 8.3.

Departures by residents in ECE,

1988-2003. Sources: ŠÚSR, 1991-2005; HNTO,

2003; CNTO, 2004; PIT, 2004.

There were a number of reasons for these

increases, linked to the removal of the Iron

Curtain, the growth of business tourism in newly

opened economies, and the generation of

trans-border shopping tourism from Germany

and Austria. The period 1996-1997, however,

was something of a watershed for the visitor

inflows to all ECE countries. Slovakia experi-

enced a similar trajectory to its neighbours,

although

its

decline

in

numbers

was

less