Information Technology Reference

In-Depth Information

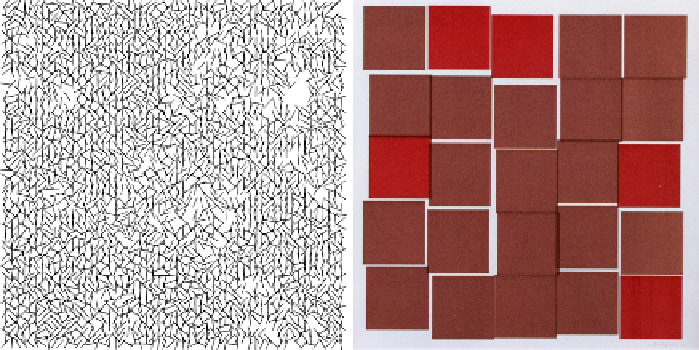

Fig. 3.4

Vera Molnar.

Left

:

Interruptions

, 1968/69.

Right

:

25 Squares

, 1991 (with permission of

the artist)

ilar in style to what many of the concrete artists had also done. The switchover

to the computer gave her the opportunity to do more systematic research. (“Visual

research” was a term of the time. The avantgarde loved it as a wonderful shield

against the permanent question of “art”. Josef Albers and others from the Bauhaus

were early users of the word.)

The

Interruptions

of Fig.

3.4

happen in the open spaces of a square area that is

densely covered by oblique strokes. They build a complex pattern, a texture whose

algorithmic generation, simple as it must be, is not easy to identify. The open areas

appear as surprise. The great experiment experienced by pioneers of the mid-1960s

shows in Molnar's piece: what will happen visually if I force the computer to obey a

simple set of rules that I invent? How much complexity can I generate out of almost

trivial descriptions?

3.3.2 Charles Csuri

Our second artist who took to the computer is Charles Csuri. He is a counter exam-

ple to the “only mathematicians” predicament. Among the few professional artists

who became early computer users, Csuri was probably the first. He had come to

Ohio State University in Columbus from the New York art scene. His entry into the

computer art world was marked by a series of exceptional pieces, among them

Sine

Curve Man

(Fig.

3.5

,left),

Random War

, and the short animated film

Hummingbird

(for more on Csuri and his art, see Glowski

2006

).

Sine Curve Man

won him the first prize of the

Computer Art Contest

in 1967.

Ed Berkeley's magazine,

Computers and Automation

(later renamed to

Computers

and People

), had started this yearly contest. It was won in 1965 by A. Michael Noll,