Agriculture Reference

In-Depth Information

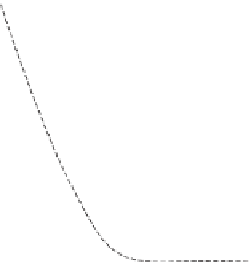

Stand-thinning fire regime

50

Individual fire

40

Natural

landscape

30

Perturbed

landscape

20

10

0

0.1

10

Gap size (ha)

10 0 0

Fig. 5.9

Projected gap size in mixed conifer forests of the Sierra Nevada under historical

conditions and perturbed conditions due to a century of fire suppression policy that has excluded

fire

.

(From Keeley & Stephenson

2000

.

)

These forests require management that restores historical fire regimes or utilizes

mechanical thinning to reduce current fuel loads (Franklin

et al.

2006

). These

approaches sound like simple alternatives but there are untold problems behind

both. Prescription burning is a viable option in some parts of California, but due

to human demographics, it is not widely applicable in many areas highly frag-

mented by development. Additionally, atmospheric circulation in most of these

ranges is closely linked with foothill and valley communities and as a consequence

air quality constraints greatly limit the window of opportunity for prescription

burning. Mechanical thinning (i.e. logging) is perhaps the only option in many

forests, but it is costly, particularly if the prescriptions focus on removing those

tree sizes most responsible for fire hazard. Mechanical thinning projects can pay

for themselves, but usually only if large trees are harvested. This scenario creates a

dilemma because removing large trees promotes further in-growth of saplings and

may exacerbate the fire hazard problem, requiring future mechanical thinning at

shorter intervals.

In chaparral, fire suppression has not been effective at eliminating fires. On the

basis of our understanding of historical burning patterns it is apparent that

contemporary fire regimes are not qualitatively different from historical fire

regimes (Keeley

2006a

). However, fire frequency has increased with demographic

growth and the human subsidy of fires has greatly increased fire frequency.

Thus, the lower foothills and coastal plains have not experienced fire exclusion

and in fact the landscape burns far more frequently now than historically was

the case (Keeley

et al.

1999a

). This does not imply that fire suppression has had

no impact. Indeed, without suppression over the past century this landscape

would have burned at a much greater frequency than was the case historically.

Fire management of this landscape is particularly difficult because it is also the

region of greatest human development. The primary management dilemma is