Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

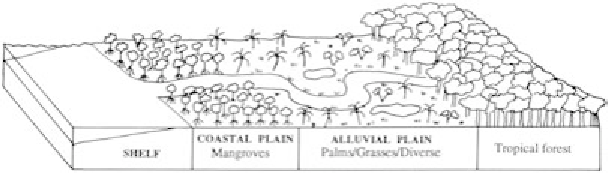

Figure 7.6

Reconstruction of Miocene landscape and communities of northwest Amazonia.

From Hoorn 1993. Used with permission from Elsevier Science Publishers, Amsterdam.

incursions deep into the interior were no longer possible. Later, eustatic-

induced regressions of ocean levels along the Bragança Peninsula of Brazil

caused seaward movement of mangroves 1130-1510 and from 1560 into the

1800s, correlated with the Little Ice Age (Cohen, Behling, and Lara 2005;

Cohen, Filho, et al. 2005).

Some of the same information used to reconstruct the origin and spread

of New World ecosystems is also applicable to tracking the history of indi-

vidual lineages and the physical environment. As noted previously, all such

applications of paleobotanical data benefi t from incorporating faunal stud-

ies to generate biotic histories, and from integrating geological and climatic

data to provide insight into ecosystem evolution. To illustrate the point, pa-

leodrainage patterns in the Amazon Basin are revealed by sediments from

several formations from the Falcón Basin, east of the Maracaibo Basin, to

the Venezuela Basin between Caracas and Trinidad and Tobago (Díaz de

Gamero 1996). In the middle Eocene, deposits of the Misoa Delta iden-

tify a large river fl owing north into the Maracaibo Basin and draining the

Cordillera Central and the Guiana Highlands. With continued uplift of the

eastern cordillera of the Northern Andes, delta formation shifted south-

ward, as indicated by deposits in the late Eocene to Oligocene Carbonera

Formation in the Llanos region of Colombia and Venezuela. Then in the

mid-early Miocene, deposition shifted east into the northwestern part of

the Falcón Basin. With further uplift in the late part of the middle Miocene,

the river outlet moved still farther east to its present position off the coast of

northeastern Venezuela. These sediments reveal the meandering history of

the Orinoco River from the late Eocene through the middle Miocene.

Biologists are interested in inundations and shifting drainage patterns

because such shifts are among the several ways populations can be par-

titioned (geographically isolated) and reunited. Other processes at work

include orogeny, tectonics, arch formation, and disappearance of arches