Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

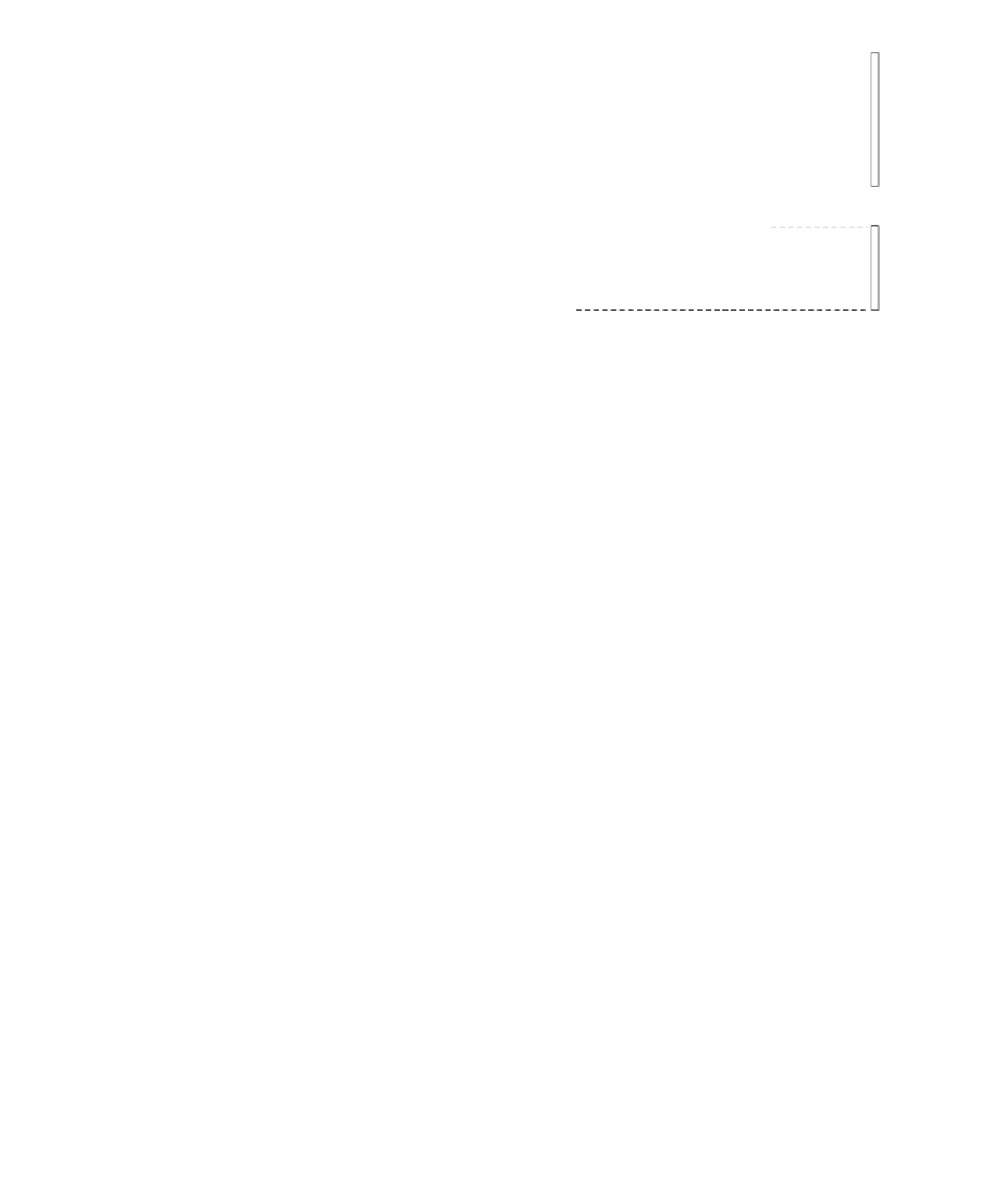

Extreme high water

Average high water

CLAY

Average summer water

SAND

Low water

PEBBLES

annual

weeds

reed

bed

Salix

shrubs

Salix

woodland

Alnus

woodland

Ulmus-Quercus

woodland

deciduous

forest

flood

plain

grass-

land

WATER

FLOODPLAIN

WITHOUT TREES

FLOODPLAIN

WITH WOODLAND

OUTSIDE

FLOODPLAIN

Figure 5.1

Vegetation zonation along rivers in relation to fl ooding frequency. (From Ellenberg 1986. Reproduced by

permission of Verlag Eugen Ulmer.)

Connectivity

and its effects on fl ows of matter and

organisms have become a major research theme in land-

scape ecology. The relation with landscape pattern is

often very complex and may range from broad-scale

fl ows that are hardly related to any landscape features

(e.g. bird migration at higher altitudes) to very localized

fl ows that are completely determined by landscape

structure (e.g. seed transport by fl owing water). Model

simulations show that in purely 'random' landscapes,

circa 60% of the space must be covered by suitable

habitat patches in order to ensure that organisms can

disperse from one side of the area to the other without

having to leave the habitat; that is, be part of a function-

ing metapopulation. In real landscapes, this percentage

can be much lower, due to the presence of

corridors

, rela-

tively narrow strips of suitable habitat that connect

patches. Simulations (e.g. Gardner

et al

. 2007 ) show

that presence or absence of corridors makes a dramatic

difference for the 'percolation' of organisms within a

landscape. One could say that corridors function as

communication channels within the landscape.

However elegant this concept may be, the recognition of

corridors in reality is not easy and may differ from one

species to another. Hedgerows may be corridors for

beetles, but for ospreys the river that fl ows through a

hedgerow landscape may be an appropriate corridor.

5.3 FLOWS BETWEEN LANDSCAPE

ELEMENTS

Even in the second half of the twentieth century, most

landscape ecologists had a rather static view of their

subject. Landscapes were described and classifi ed on

the basis of certain parameters which might refer to

exchange processes, but explicit incorporation of fl ows

of matter and movement of organisms was not nor-

mally done. This changed in the last few decades of the

twentieth century, when it became increasingly clear

that spatial arrangement is a fundamental feature of

terrestrial landscapes. Ecosystems in sites with similar

abiotic conditions, but differing in spatial arrange-

ment, may develop in entirely different ways because

of differences in the infl ow or outfl ow of resources,

and/or different immigration rates of preys and com-

petitors linked to spatial organization.