Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

Hence climate change in many ways is simply bringing

the requirement for improved conservation planning

and management into sharper focus. However, Heller

and Zavaleta (2009) also found that, for many recom-

mendations, there is little specifi city about how, by

whom and under what conditions they can be imple-

mented. In other words, most recommendations cur-

rently deal in generality rather than providing specifi c

guidance in particular situations. The problem of

moving from the general to the specifi c has been rec-

ognized often, and recently there have been attempts

to provide general checklists of issues to be considered

and adapted in the context of specifi c systems or situ-

ations (Lindenmayer

et al

. 2008 ). These include recog-

nizing the importance of landscape mosaics (including

terrestrial-aquatic linkages), maintaining the capacity

to recover from disturbance and managing landscapes

in an adaptive framework. These broad considerations

are infl uenced by landscape context, species assem-

blages and management goals and need to be adapted

accordingly for on - the - ground management. Two

important requirements are a clearly articulated vision

for landscape conservation and quantifi able objectives

that offer unambiguous signposts for measuring

progress (Lindenmayer

et al

. 2008 ).

Climate change and the resulting biotic responses

provide multiple challenges for conservation. Species

ranges are likely to shift and species assemblages are

likely to change (see also Chapters 20 and 21). The

biotic assemblage will respond to not only the direct

climatic changes but also the changed incidence of epi-

sodic events, altered fi re, fl ooding and other distur-

bance regimes, and changes in disease and pest

prevalence. Increasingly, active intervention may be

required to achieve conservation goals as currently

formulated and previous ' hands - off ' approaches to

reserve management may no longer be suffi cient

(Hobbs

et al

. 2010). Increasing levels of intervention

seem inevitable (Figure 3.2). Particularly in the United

States, approaches to reserve and wilderness manage-

ment based on the 'natural' system are under question

- what constitutes 'natural' in a rapidly changing

human-dominated world? However, if we abandon

existing norms and concepts, what will replace them?

The options include utilizing concepts such as

ecosys-

tem integrity

and

resilience

(Cole & Yung 2010 ;

Hobbs

et al

. 2010). Climate change will not lessen the

requirement for traditional place-based management

(set-aside reserves, etc.) but may render it insuffi cient.

If a reserve has been designated because it contains a

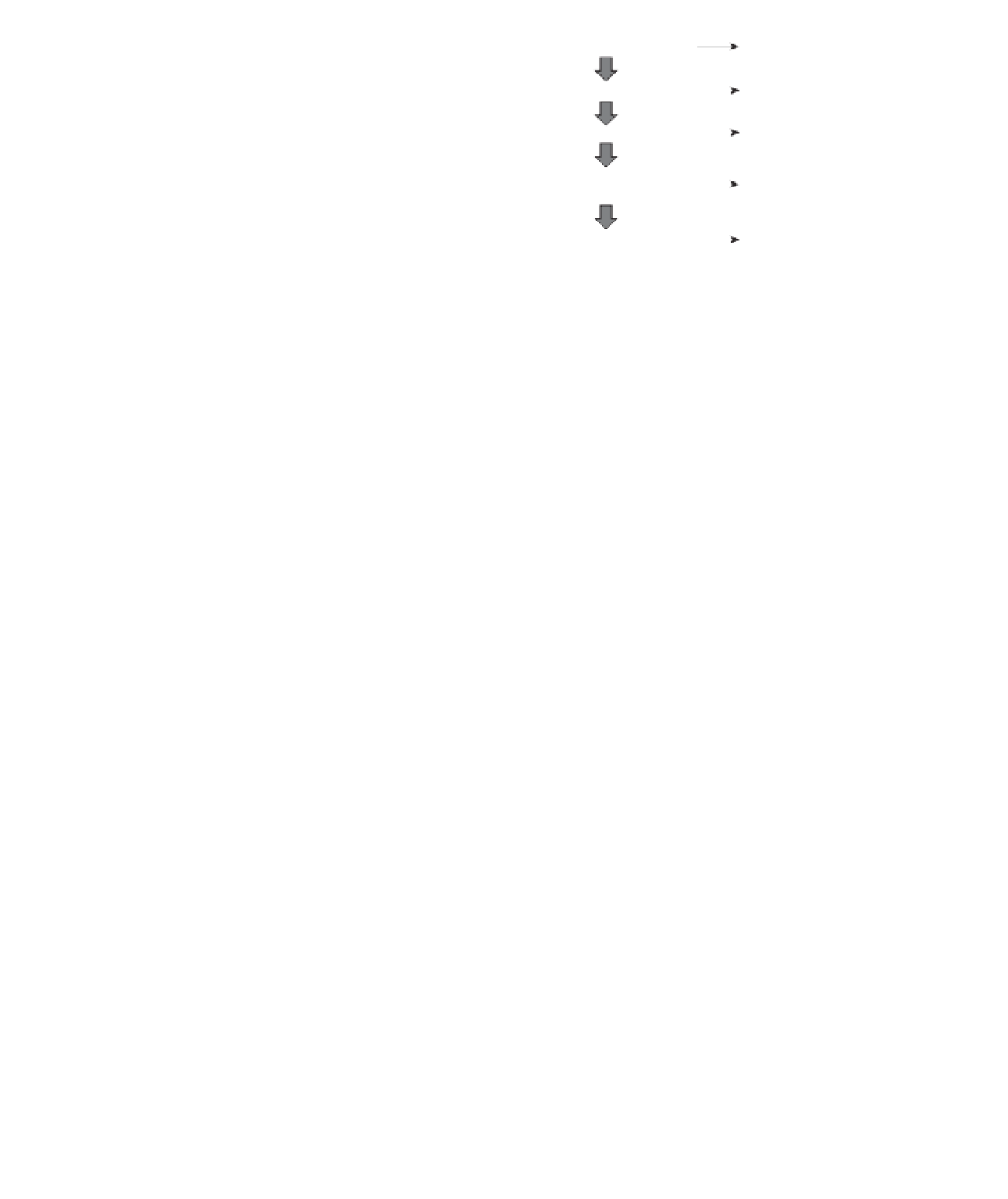

Protection of species

and places

Conservation

Removal/amelioration

of threats

Passive restoration

Active alteration of abiotic

and/or biotic characteristics

Active restoration

Designer ecosystems

Ecosystem engineering

Creation of new systems

for desired 'services'

Managed relocation/

assisted migration

'Anticipatory' conservation

Figure 3.2

Increasing levels of intervention, from

traditional ' preservation ' - focused conservation through

active restoration and design of ecosystems which fulfi l

specifi c purposes.

particular species or set of species, what happens to

that reserve if the species no longer occur there because

they have moved elsewhere in response to a changing

climate? And where do these species move to? The

reserve system worldwide is patchy and unrepresenta-

tive, and there is increasing recognition that the

surrounding landscape can be very important in deter-

mining the overall success of local conservation efforts

(Daily

et al

. 2001 ; Ranganathan

et al

. 2008 ). This is

likely to become even more relevant under climate

change.

Determining landscape confi gurations which facili-

tate movement of species under threat from changing

climates will be an important process. However, beyond

that, there is also increasing discussion of the desira-

bility and practicality of deliberately moving species

in anticipation of changing climates. The process of

assisted migration or managed relocation remains con-

troversial, although there have been recent attempts to

consider the circumstances under which it might or

might not be considered (Hoegh-Guldberg

et al

. 2008 ;

Richardson

et al

. 2009). Given the uncertainty sur-

rounding the rate and direction of climate change at

local and regional scales, it will remain diffi cult to

predict future ranges for many species with any degree

of certainty. However, some groups are already con-

ducting such relocations: for instance,

Torreya taxifolia

has been relocated by the Torreya Guardians in the

south-eastern United States (Shirey & Lamberti 2011).

The issues surrounding such activities are as much

ethical as ecological, and are forcing a rethink of con-

servation norms and policy (Minteer & Collin 2010).