Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

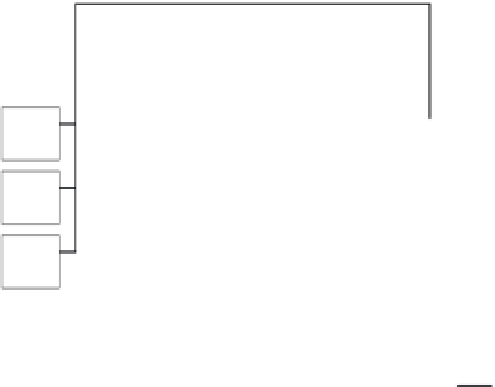

implies that habitat patches that are suitable may be

temporarily empty. For restoration purposes there is

therefore a need to identify potentially suitable hab-

itat patches, which may or may not be occupied. How

can suitable habitat be identified? Habitat models

originated in the USA in the 1970s, and were devel-

oped further in Australia in the 1980s and in Europe

in the 1990s (Kleyer

et al

. 2000). The focus has been

on statistical models and on expert-based habitat

models. A major contribution to nature conservation

planning resulted from relating habitat models to

geographic information systems (GISs). Corsi

et al.

(2000) combined deductive and inductive approaches

to identify species distributions (see Fig. 6.5). The

deductive approach uses known species' ecological

requirements to extrapolate suitable areas from the

environmental variable layers in the GIS database. The

inductive approach is used to derive the ecological

requirements of the species from locations in which

the species occurs. These two approaches can contribute

to habitat suitability mapping. Concerning statistical

models, recent publications favour logistic regression

as compared to discriminant analysis. Note that stat-

istical habitat models imply the assumption that the

observed occurrence is in equilibrium with the envir-

onmental factors and their spatial arrangement. Clearly

setting the preconditions necessary to transfer hab-

itat models in time and space, which then have to be

validated, is seen as a prerequisite for application in

6.3 Suitable habitat patches

Effects of habitat fragmentation on birds and mam-

mals in landscapes with different proportions of suit-

able habitat have been reviewed by Andrén (1994).

Many studies he referred to have found that com-

munities or populations of single species in small

patches were not random samples from large patches.

A more fine-tuned analysis showed that studies in

which an effect of area and/or isolation on species

number or density was found were from landscapes

with highly fragmented habitat, whereas those yield-

ing results that were not different from those predicted

by the random-sample hypothesis were mainly from

landscapes with a larger proportion of suitable habitat.

In this respect, there was no difference in principle

between mammals and birds, nor between resident birds

and migratory birds. The review indicated that there

might be a threshold in the proportion of suitable hab-

itat in the landscape, above which habitat fragmenta-

tion is pure habitat loss. Indeed, a review by Fahrig

(2003) has shown clearly that it is most important to

distinguish between effects of habitat loss and effects

of habitat fragmentation, because habitat loss has large

negative effects on biodiversity, whereas the effects

of habitat fragmentation are rather weak and may be

positive or negative.

In the metapopulation approach both immigration

and local extinction are normal phenomena. This

A priori

knowledge

GIS

layer

Species-

distribution

map

Species-environment

relationship

Spatial

model

GIS

layer

validation

validation

Fig. 6.5

General data flow of

the two main categories of GIS

species-distribution models,

indicating inductive and deductive

approaches which in combination

can be used to identify suitable

habitat. After Corsi

et al

. (2000).

Reproduced by permission of

Columbia University Press.

GIS

layer

Analysis of

species-environment

relationship

validation

Observations

inductive

deductive

SPECIES