Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

the maximum prior biodiversity, within maximized

ecosystem services, then this term is again useful. The

second level is often called

rehabilitation

and con-

sists of the restoration of certain ecosystem functions

(Mitsch & Jørgenson 1989, Wali 1992), such as the

reduction of flood risks by creating the development

of water-retention systems or restarting peat growth

to fix CO

2

in peat layers. This option would make parts

of the landscape as a whole more natural, but it would

not necessarily result in a significant increase in

biodiversity in the whole landscape. The third level

is sometimes called

reclamation

and consists of

attempts to increase biodiversity

per se

. The landscape

as a whole would benefit from an implementation of

such measures on a large scale but it usually does not

contribute much to the protection of endangered red-

list species. The definition given by Bradshaw (2002)

of 'making the land fit for cultivation' is probably the

easiest to comprehend, and most widely applicable.

The above-mentioned goals are generally associated

with different

scales

, especially in densely populated

areas where most restoration activities take place.

Although it is technically sometimes possible to really

recreate some former communities (true restoration)

on a local small scale and at high cost, this is gen-

erally impossible at the landscape scale because of land-

use conflicts, long-distance effects of other activities

and lack of public support. Reclamation is often the

only realistic option at this scale. Rehabilitation

seems to be practical at an intermediate scale, often

as a network within a certain landscape, for example

riparian restoration (Kentula 1997). We suggest that

simple recreation of past species lists is unlikely to

succeed:

process

and

connectivity

must be taken

fully into account, along with

biodiversity

.

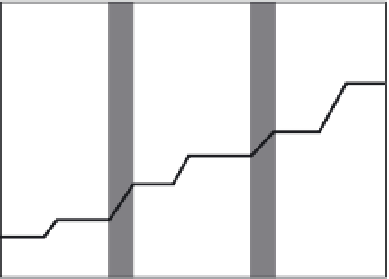

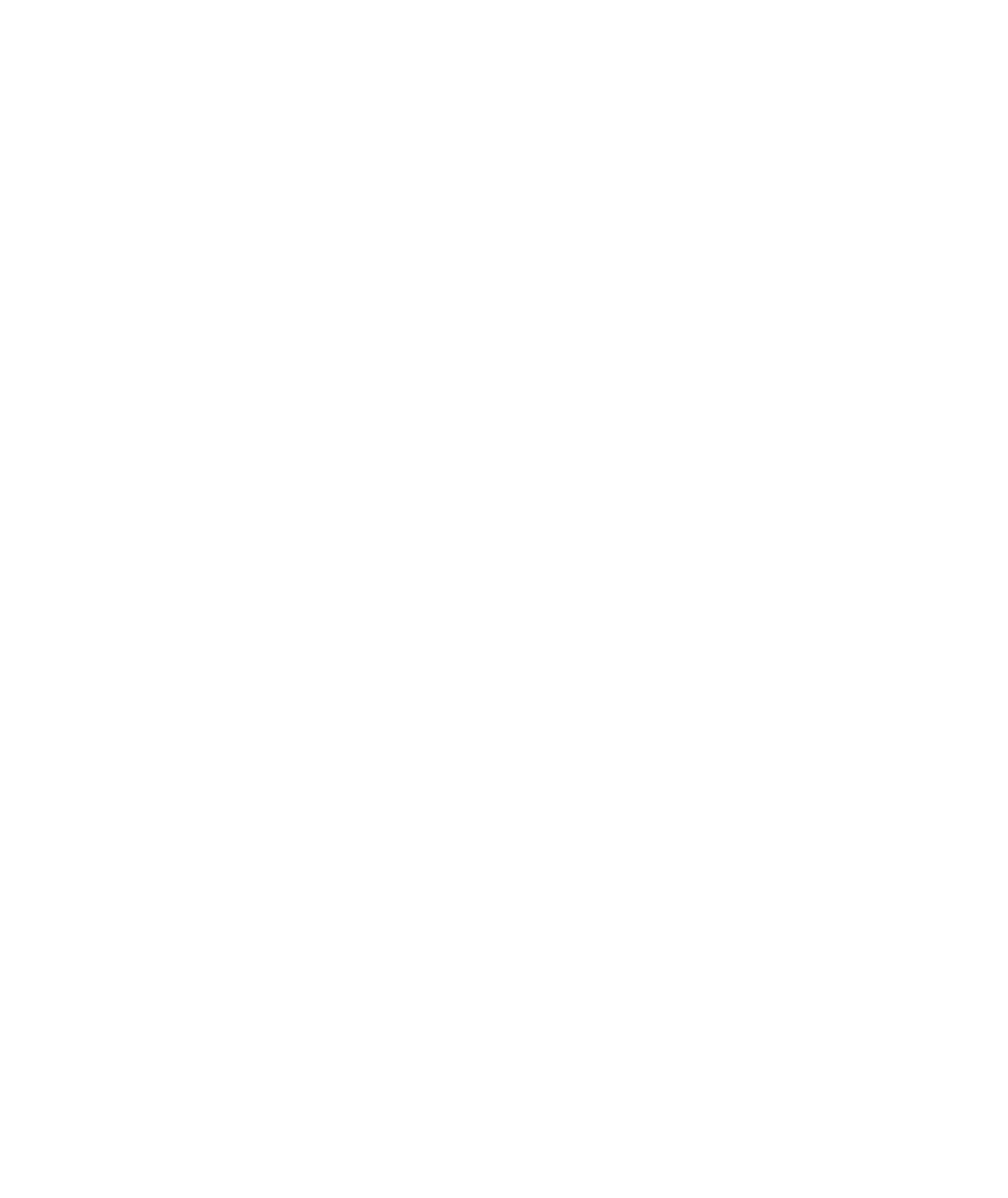

A useful way of separating the reclamation and

restoration definitions is to base them on the types

of barrier that need to be crossed. It is possible to

relate these terms to the conceptual arrangement of

degraded, recovering and restored ecosystems in the

light of a schema defined initially by Whisenant

(1999) and further developed by Hobbs and Harris

(2001), as illustrated in Fig. 1.4. Here, a number of

putative stable ecosystem states, from degraded to

intact, are related to ecosystem function. There are

two principal barriers between degraded and restored

(intact) systems. The first are abiotic barriers, which

Abiotic

Biotic

Requires

physical

modification

Requires

biological

modification

Requires

improved

management

Fully

functional

1

2

Ecosystem

attribute

3

4

5

6

Non-

functional

Reclamation

Restoration

Degraded

Ecosystem state

Intact

Fig. 1.4

Relationship between measured ecosystem

attributes, biotic and abiotic barriers, and the processes

of reclamation and restoration (modified from Hobbs &

Harris 2001).

could be a lack of appropriate topology, contaminated

substrate, too-high or -low a groundwater table, little

or no organic matter, etc. These barriers all require

physical modification to bring the systems to a new

level of stability associated with a new 'higher' level

of function. The second barrier is biotic; this may be

as a result of a lack of appropriate species or inter-

action between them and abiotic components. Again,

active modification allows these barriers to be overcome.

We suggest that the first transition is the reclamation

phase and the second is the restoration phase of a pro-

gramme designed to restore ecosystem function and

structure. Rehabilitation may be regarded as the

transition from level 4 to level 3 on Fig. 1.4; that is,

without crossing a significant threshold leading to a

new, self-sustaining, ecosystem trajectory.

This gives us some clear goals to aim at, such as

the re-instatement of a hydrological regime, or re-

introduction of a keystone species. We must go further

than simply measuring one feature or attribute. There

are often conflicting interests from groups favouring

plants, birds or animals, for example. The techniques

designed to restore a species-rich meadow, with late

cutting once a year, may be totally inappropriate

for invertebrate populations, dependent on bare sub-

strates for nesting and nectar plants for feeding: the

late cut turns a feast into a desert overnight.