Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

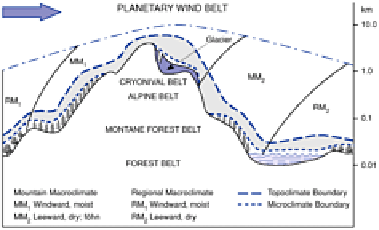

Figure 25.9

The scale and variety of mountain climates.

Mountain topoclimate (shaded) separates myriad surface

microclimates from the broader mountain macroclimate. The

logarithmic scale refers to the thickness of each layer, not to

the absolute altitude.

Source: Modified from Barry (1992).

through condensation levels, either in the waves or in isolated

rotors

, and - in stable air -

evaporates on the descending limb, leaving stratiform lee wave or rotor clouds (Plate

25.4).

Fall winds

describe air currents descending leeward slopes, distinguishable by their

thermal character and development according to diurnal, seasonal or synoptic conditions.

Warm-air downflow is generated under particular lapse rate conditions which lead to

warming on descent known as the

föhn

(Alps) or

chinook

(Canadian Rockies) effect.

This occurs when stable air loses moisture over the barrier and descends at a dry

adiabatic lapse rate with an absolute gain in temperature (Figure 25.10). Most currents

adiabatically warm on descent but are less powerful mechanically and thermally. The

föhn or chinook occurs seasonally in most mountain systems; the native Canadian term

means 'snow-eater', underlining their important environmental influences as warm,

desiccating winds.

Contrasting

cold

-

air drainage

occurs as gravity flows of denser air, such as the

bora

(Adriatic Sea) or

oroshi

(Japan). In their simplest form they are currents of cold air

ponded up on windward slopes and draining through passes or other topographic lows.

Cold air is also