Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

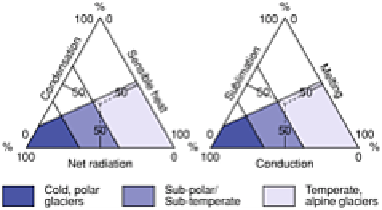

Figure 2

Ternary diagram of glaciers classified according to

principal energy sources and sinks.

Source: After Andrews (1975).

at first, reaching 0·2 within a few days, but slows considerably thereafter.

Firn

, translated

from German, means literally snow 'from last year' but its typical density of 0·4 is rarely

reached so quickly. It increases faster under higher temperatures and accumulation rates,

exceeding 0·8 within 10-20 a in alpine glaciers but can take 150-200 a in polar ice.

ICE SHELVES AND SEA ICE

Numerous alpine glaciers in Alaska, Chile and New Zealand terminate in

tidewater

-

mostly in fjords - but temperate ice does not possess sufficient tensile strength to allow

them to float. Instead, tides cause the ice to flex and

calve

or release floating icebergs. By

comparison, ice shelves extend from polar ice sheets whose colder ice is stronger. The

Ronne-Filchner and Ross ice shelves, covering 0·75 million km

2

and 0·45 million km

2

respectively, are the largest of a suite of ice shelves fringing 30 per cent of the Antarctic

coast (see Colour Plate 13 between pp. 272 and 273). They account for over 7 per cent of

Antarctic Ice Sheet area. Shelves develop as

piedmont glaciers

fan out into coastal

lowlands from outlet glaciers and float seawards of a

grounding line

when water depth

reaches about 90 per cent of ice thickness, determined by the greater density of sea water

(Plate 15.2). Shelf ice is implicated in glaciomarine processes outlined later.

Sea water freezes at −1·91° C and, except where rapid freezing occurs, loses most of

its salinity on freezing. Initial freezing forms small, crystalline platelets known as

frazil

ice

which coalesce rapidly. A mean thickness of 2·5 m can develop in a single winter and

melt as quickly. Multi-year ice, which is tougher than single-year ice, subsists in less

extreme conditions by basal accretion and surface melt.