Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

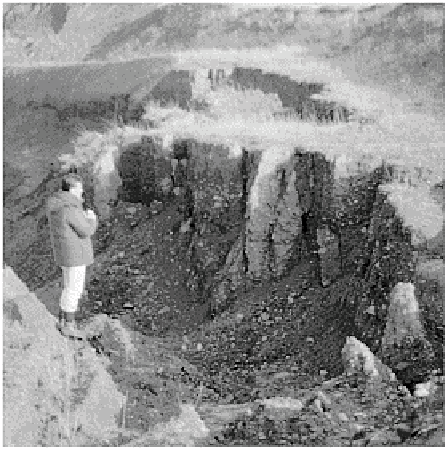

Plate 13.12

Toppling of cohesive, glaciofluvial gravels in a

quarry face, after tension cracking behind the working face

(right). The figure is standing on a toppled block.

Photo: Ken Addison.

DEBRIS FLOW HAZARD AND STRUCTURAL DAMAGE

human impact

Debris flows are among the most unpredictable, fast-moving forms of mass wasting

process, capable of self-regeneration in transit. For these reasons they pose particular

hazards to human settlements and structures. They are initiated by a wide range of stimuli

- landslides, seismic activity, intense rainfall, rapid snow or glacier melt, water eruption

(e.g. a bursting pipe), volcanic eruption, etc. - depending on the critical condition of

slope materials at the time of potential failure. Their essential requirement is rapid

fluidization of granular debris, hence the rapid water delivery and/or high-porosity debris

components listed. They are common on arctic and alpine slopes (see Chapter 25).

Explosive eruptions on ice-capped strato-volcanoes generate some of the most

spectacular, destructive debris flows and provide their own granular debris in the form of

ash falls.

Debris flows and

lahars

(volcanic mud flows) triggered by the Nevado del Ruiz

eruption in Colombia (1985) swept over tens of kilometres and claimed more than 25,000

lives. The 1980 Mount St Helens eruption in Washington State (USA) claimed few lives

but debris flows travelled over 20 km along the Toutle river valley. The ty pical sequence

of events started with an earthquake, triggering the eruption via a major landslide which

opened up the blast vent Unconsolidated slope materials were disturbed by both shocks