Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

pickup truck, and he visited with whomever was there.

In maybe five minutes he'd found that some old friend

or relative was a mutual acquaintance (sometimes I

wonder if he invented these people), and reminis-

cences followed. We were soon invited to join in any-

thing from dinner to a hunt for just what we came

after, or we were referred to someone else who could

supply it. I suppose the best introduction to country

folks who know about log houses is, finally, being obvi-

ously country folks yourself — not hobbyists — with

calluses to prove it.

Once found, it may take a lot of persuasion for the

owners to part with the structure in question. They

may have plans for it, but get them to thinking about

selling it, and that will work on their minds. Check

back often. An example is a man I worked with in

Memphis who'd been after his cousin in Pulaski

County, Tennessee, to sell him one of several cabins

and log barns on the extensive old family farm. The

cousin had plans to restore them all. Then a heart

attack made it clear he would never get to these proj-

ects in whatever remained of his life. He called the

Memphis cousin and told him to come take his pick.

The result was a chestnut and poplar cabin with

28-inch-wide hewn logs, moved and restored as a

guesthouse. Those were among the widest logs I've

ever seen, although I frequently work with 20- to

24-inch ones.

Surprises

I caution again of the work and danger involved in this

project. Start looking for the red flags right away:

• termite damage

• water damage and rot

• logs beyond repair

• caved-in basement or foundation

• loose chimney stones or bricks

• disintegrating windows or doors

• sagging floors

• decayed joists

• bowed rafters

• decayed roofing or roof decking

• worn-through floors

The first enemy of your restoration is the very work

of time that may appeal to you most. Unless your find

has been boarded over and roofed with tin, the mate-

rials can be pretty crumbly. A log house can look

sturdy as it stands but come to pieces when disman-

tled. Most alarming is the way bark and rotted sap-

wood flake off, leaving you with six-inch chinking

cracks where the originals were two inches.

Pine and poplar rot from the outside, and logs like

these may have massive, sound heartwood. But oak

and chestnut usually start decaying from inside, when

water gets into check cracks. These logs look better

than they are. Often a thin shell hides a spongy, rotted

core.

Check your prospect for soundness. If a log looks

rotten or termite infested, it probably is. Held in place

by the comfortable stresses of years, logs and beams

can look solid when they're not. Poke, pry, hammer on,

and stick your knife into everything you can reach

until you're satisfied. I recall how solid an unroofed

chestnut log pen in Virginia looked. Most of the logs

were mush inside.

A house that has no roof left is a risk. The old, dry

logs go to pieces very quickly when they are exposed

to weather. As little as three or four years uncovered

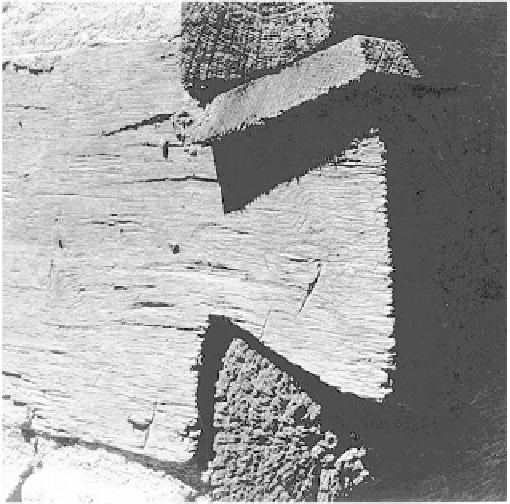

When notches, such as this full-dovetail one, are split off, it is some-

times necessary to reshape them and use a wood block for a spacer.

This one was later trimmed off flush to fit.