Civil Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

to a common dimension. Some finely built log houses

in the East, with four hewn faces, reflected the

builders' European and Scandinavian backgrounds.

I prefer the broadaxe over the adze, which is more

of a finishing tool. As far as I know, nobody manufac-

tures these axes now, except for some rare and expen-

sive hand-forged collector's items. They can still be

had for a price at junk shops and antique sales. The

axe head can be handled for right or left use, and these

handles

are

different.

To hew, you stand alongside the log with the flat

side of the axe to the wood, and it's on the same side

with you, very close to your toes. Your knuckles also

take a beating unless the axe handle is bent away from

the log. So, with the bend away from the flat side, that

means a different handle if you're left- or right-handed.

Novices usually devise their own variations of the

basic straight-down swing, but anyone who does

much axework soon returns to it. Years ago I thought

I'd discovered something by using a right-handed

axe at a 45-degree angle, hewing on the other side of

the log with my left-handed swing. I soon abandoned

that strenuous game, and I suggest you forget such

variations. The heavy axe is more efficient used

straight down with gravity working for you instead of

against you.

A good man often hewed a dozen logs a day using

the old method, and lived. I hew two or three, then

find something else to do for a while. A good day's

work for tie-hackers was also about a dozen a day,

hewed on four sides but only eight feet long. I hear

tales of hackers turning out 20 ties a day, but I would

have to see it myself.

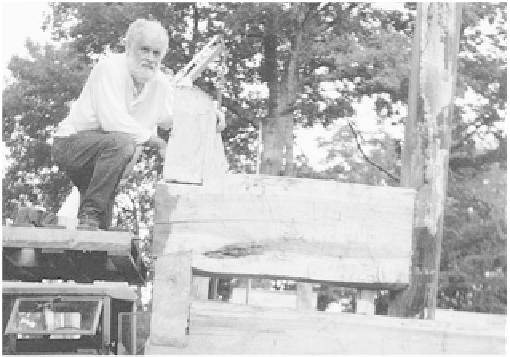

Craftsman Wilson McIvor helped us adze the faces of these huge sawn

poplar logs for a new log house near Nashville, Tennessee. These logs

were as wide as 34 inches.

First, score-hack the log down one side, every six

inches or so with an axe. You can stand on the log for

this, or chop from alongside, avoiding your kneecap.

Some hewers snap a chalk line along the log as a

guide and hew to the line after they've scored to it first.

Most logs aren't straight enough to make this easy, so

other hewers sort of chop a line in the bark. I just eye-

ball it and make a second pass to take out humps.

You'll need two passes at the thick butt end anyway.

You can also chainsaw these scores to a snapped

chalk line. Master craftsman Peter Gott, in North

Carolina does this neatly and efficiently. I have always

eyed my logs, and chopped more than sawed. Then

there are a couple of ways to go. One calls for splitting

out the chunks, or “juggles,” with the plain axe (poll

axe, felling axe, “choppin” axe) then making a pass

with the broadaxe. I score deeply, making a notch if

necessary, then slice off the juggles with the broadaxe.

Either way, you eventually assume the broadaxe

stance, swing straight down to hit the log at about

45 degrees, and cut off everything that doesn't look

like a hewn log. Lay tough boards under, to keep your

axe out of the rocks (after a couple of logs, there'll be

plenty of juggles to pad the ground underneath). Early

hewers set the log up high on blocks and hewed almost

straight down with the broadaxe, which had a short

(two-foot) handle for precision. I like the later three-

foot handles, which I usually make myself, because

you get more swing and take off more wood at a stroke.

The longer handle does require more accuracy.

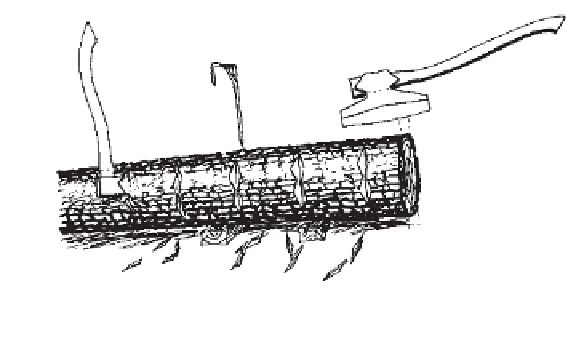

The log to be hewed was often held in place by a log hewing dog. First

it was scored (notched), sometimes to a snapped chalk line, then sec-

tions (juggles) were sliced off with the broadaxe.