Environmental Engineering Reference

In-Depth Information

What type of

material (e.g.,

sand or clay) is

the contaminant

flowing through?

How long do specific

contaminants last in

certain geologic

environments before

they physically

degrade?

From the release

point, what is the

direction of

groundwater flow?

In humid climates, groundwater flows into surface water, and this process creates the

need to know more about the local geography of the water resources, particularly the

locations of surface streams, lakes, and wetlands. The locations of streams and their flow

patterns are required to determine the potential for contaminant transport and the larger-

scale environmental problems that may result. And, since the water within lakes and wet-

lands consists of groundwater above the water table, knowledge of their flow patterns is

also necessary to obtain a complete picture of the contamination potential.

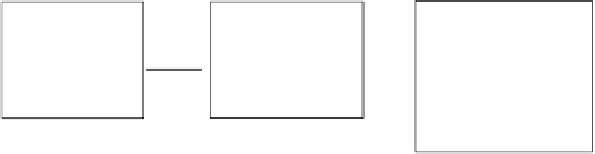

The three maps in Figure 1.5 show the outcome for generalized categories of contami-

nants spilled from selected surface locations within the Rouge River watershed in the Great

Lakes region. There are five contaminant categories that have been selectively investigated.

These categories include

dense nonaqueous phase liquids

(DNAPLs—chlorinated sol-

vents),

light nonaqueous phase liquids

(LNAPLs—gasoline compounds),

polycyclic aro-

matic hydrocarbons

(PAHs—oil compounds),

polychlorinated biphenyls

(PCBs) and a

group of several heavy metals, including chromium and lead. Only those locations where

the near-surface geologic environments have a high migration potential are shown (sand

and moraine). At the top left, the map shows buffers around some of these locations, with

the buffer sizes representing the average distance these contaminants traveled based upon

measurements taken at their points of release These buffered sites were overlaid (symbol-

ized by the “+”) on the surface stream network map to the right (including all first-order

streams and higher) within the watershed. The composite map shown below the arrow

indicates the areas where there are intersections between the average contaminant extent

and a stream channel. To avoid map clutter, the circles represent a sample of some of the

locations where highly toxic DNAPL compounds contaminated groundwater in the sand

and moraine geological units.

Inspection of the contaminant sites and surface stream maps indicates there are numer-

ous other sites where contamination within groundwater has the potential to migrate

to surface water within a few days. This outcome is likely due to the high higher flow

rates within the sand and moraine units in this watershed and the high drainage den-

sities within these same units. At this geographic scale, the hydrologic cycle flows fol-

low these pathways: soil > groundwater > low order surface streams > higher order surface

streams > Great Lakes. Some persistent contaminants such as tetrachloroethene (a com-

mon dry cleaning chemical) and chromium VI (the compound used in chrome plating)

will travel along with the water. The lesson demonstrated here is that by omitting the

linkage between groundwater and flowing surface water, the consideration of ecological

impacts to the larger region of the Great Lakes may not occur.

1.4.3 Theme #3: Industrial Property Abandonment, Contamination, and Risk

We spoke earlier of the decentralization of the automobile industry that began in the

1950s. This trend has accelerated in recent years, as a geographic shift of production

from Michigan and other parts of the upper Midwest continues southward and to other

countries. In addition, so-called “transplants”—foreign nameplate companies producing

Search WWH ::

Custom Search