Biology Reference

In-Depth Information

use stored food to survive during the winter

(Pravosudov & Smulders, 2010). The scale

of storing is prodigious. In some titmice an

individual bird may store between 100 000

and 500 000 tiny seeds during a winter,

each in a separate place (Pravosudov, 1985;

Brodin, 1994).

Stored food can be thought of as

analogous to body fat, stored up in times

of plenty and used in times of scarcity

(Hitchcock & Houston, 1994; Pravosudov &

Lucas, 2001). Some species, like the

nutcrackers, use their stores over a whole

season, whilst others, such as some of the

Paridae, use them on a shorter time scale of

days or weeks, perhaps as a strategy for

overnight survival in cold weather.

Ornithologists used to assume that stored

food was communal property that improved

the survival of the group, partly because it

seemed inconceivable that birds could

actually remember the huge number of

places in which they had stored food. After

all, many of us have difficulty remembering

where we have left one bunch of keys!

However, if hoarding has a cost, then free-

loaders that did not pay the cost of hoarding

but reaped the benefits would replace

hoarders in a population (Andersson & Krebs,

1978). Hoarding is advantageous only if the

hoarding individual gains from its hoard

more than do others in the area: one way of

gaining this advantage would be for hoarders

to remember the locations of their stores.

This evolutionary argument has

stimulated many studies of the memory of

scatter hoarding birds (Brodin, 2010) that

have revealed a remarkable story linking

ecology, behaviour and neuroanatomy. In an

ingenious winter field experiment, Anders

Brodin and Jan Ekman (1994) offered

individual willow tits in Sweden 20 sunflower

seeds labelled with a radioactive isotope of

sulfur (

35

S). The birds stored the seeds in their home range. The radioactive sulfur was

incorporated into growing feathers when the individuals retrieved and ate the labelled

seeds, so Brodin and Ekman could work out which birds in the flock recovered the seeds,

and when they did so, by autoradiography of growing feathers (Figure 3.7). The results

Food hoarding for

short-term or

long-term stores

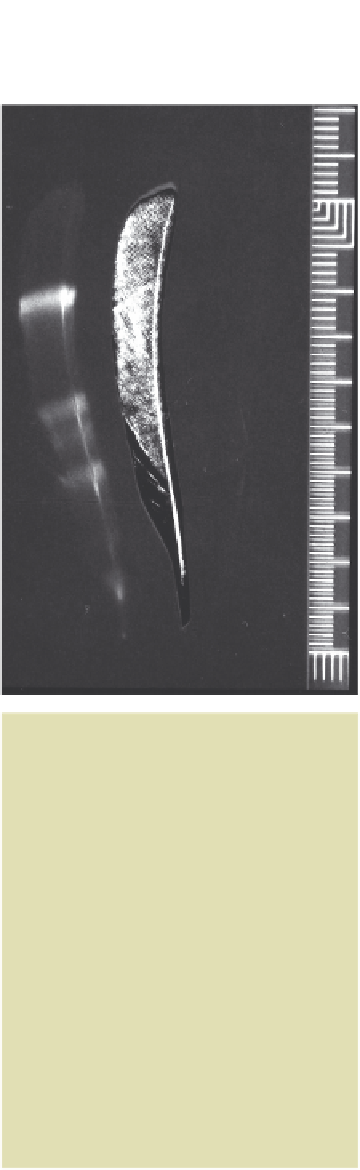

Fig. 3.7

This pair of pictures shows

an autoradiograph (left) and a

photostat (right) of a willow tit tail

feather. The upper edge of the dark

bands on the autoradiographs

indicate that the owner of the feather

ate a radioactive labelled seed on that

day, the sulfur having been

incorporated into a growing feather.

Feathers were induced to grow by

pulling out the original, and a

replacement grows over the next

40 days. The right hand, photostat,

images show faint horizontal lines

that are daily growth bars. (Brodin &

Ekman, 1994). Reprinted with

permission from the Nature

Publishing Group.